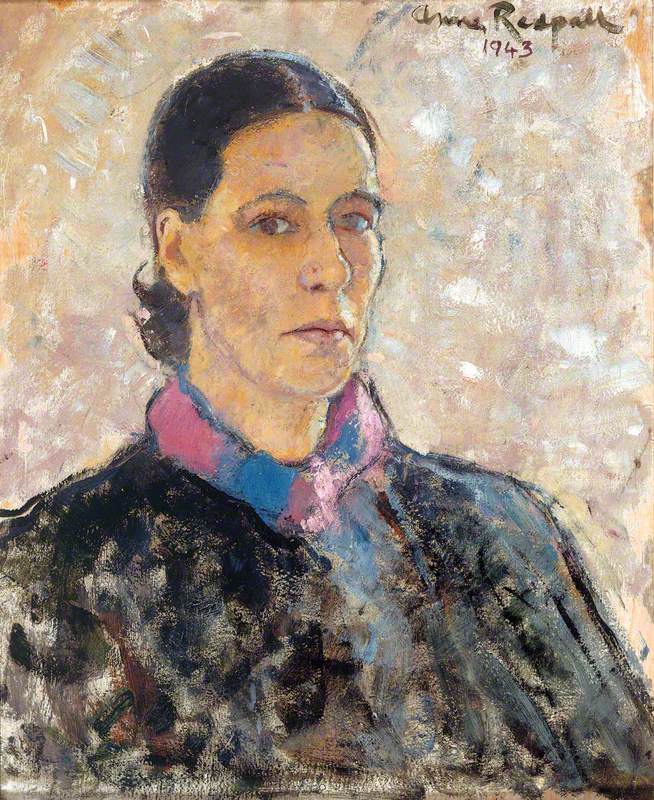

Among the seventeenth-century paintings in London's National Portrait Gallery is a remarkable self portrait by Mary Beale of c.1666. She is resplendent in a silk gown, palette hanging on the wall behind her, one hand resting on an unfinished canvas of her two young sons.

For Beale, as for many early women artists, her vocation was prompted by her family environment. Her father was an amateur artist and miniature painter and, when she married, it was to a man who had been fascinated by painting long before they met: Charles Beale. However, Charles' best-known surviving works today are his notebooks, which give us a glimpse through his wife's studio door into the life and work of a professional woman painter in post-Restoration London.

It is not known how Mary Beale trained, although she was given advice on painting by Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), one of the most distinguished artists of his day in England. Her family sat for portraits by Lely, he lent Mary his work to study, and she was later to earn a part of her income from commissions to make copies of his portraits. The Beales also owned work by Rubens and Van Dyck, and Mary's husband Charles described in his diary a family excursion to see art: 'My D. Heart, sself and son Charles saw at de Walton's in Lincoln's Inn Fields ye Lady Caernarvons pict a H. L. [half-length] done by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, in blew Sattin, a most rare faire complexion exceeding fleshy, done almost without any shadow … Also a rare head done by Holbein of ye Lord Cromwell.'

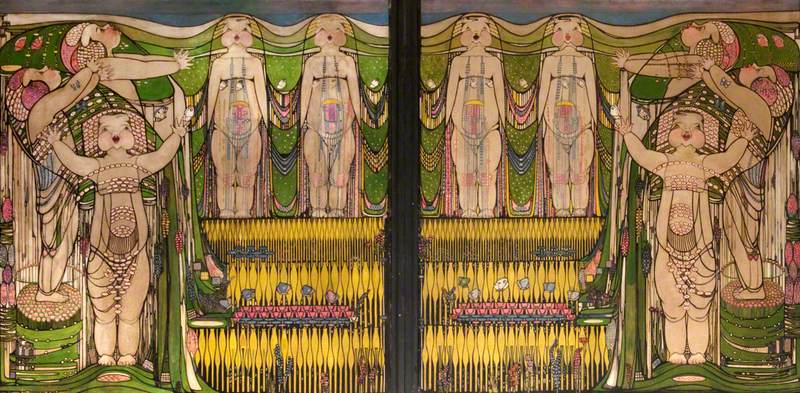

Self Portrait of Mary Beale with Her Husband and Son

1663–1664

Mary Beale (1633–1699)

At the height of her career, Mary Beale had a studio in Pall Mall, then the epicentre of fashionable life. The Beale studio, which they saw as a family affair, was a place alive with experiment. Mary's husband managed the business, and he also played an important role in supporting his wife's work through technical experiments with pigments and materials, exploring ways in which to speed up the drying time of oil paint, and to mix expensive colours more cost-effectively, in order to make commissions more profitable. Mary Beale painted on expensive imported linen, but also on sacking, and even, at times, on onion bags and striped bed ticking fabric.

The Beales' two sons helped in the studio by painting in backgrounds and drapery for portraits (although the eldest left to pursue a medical career) and there were at least two young women also working there: Sarah Curtis, who went on to set up her own business as an artist, and Keaty Trioche, who also seems to have been ambitious, as she is recorded as having bought half an ounce of one of the rarest and costly pigments – ultramarine – from Charles Beale.

Mary Beale's sitters included society figures such as Lady Leigh, who she painted as a shepherdess, albeit dressed in jewelled silks and delicately feeding a sheep a single stem in picturesque surroundings.

Beale took the composition directly from a work by Lely – it was copied by other followers of his. (Her painting of Catherine Thynne, Lady Lowther, of 1676–1677, in the Marquess of Bath Collection at Longleat, also used a composition created by Lely for his portrait of Mary of Modena, Duchess of York and later Queen of England.)

There were also portraits of the Beales' learned and cultured friends, including Edward Stillingfleet, who was to become Dean of St Paul's Cathedral and Bishop of Worcester, and Dr Thomas Sydenham, who lived near to the Beales in Pall Mall, who was from a puritan background and had been a supporter of the parliamentarians in the English civil war.

The mixture of classes and political beliefs among Mary Beale's sitters gives us a unique portrait of the turbulent times in which she lived: from civil war to the restoration of the monarchy. However, as Tabitha Barber remarked in her catalogue for Mary Beale's only solo exhibition, at the Geffrye Museum, London (1999–2000) there is a telling division between Beale's portraits: while those of great personages painted on commission made use of the stock poses of Lely, she avoided such 'artifices' entirely in the paintings she made of those close to her, which are, Barber notes 'compellingly direct, honest and sympathetic'. This latter group of paintings reflect Beale's belief that, as she put it herself, 'Flattery & dissimulation... is a kind of mock friendship'. True friendship was of religious significance, a mutually inspiring source of virtue and joy. Beale outlined her philosophy in a manuscript, Discourse on Friendship, that she dedicated to an intimate: Elizabeth Tillotson.

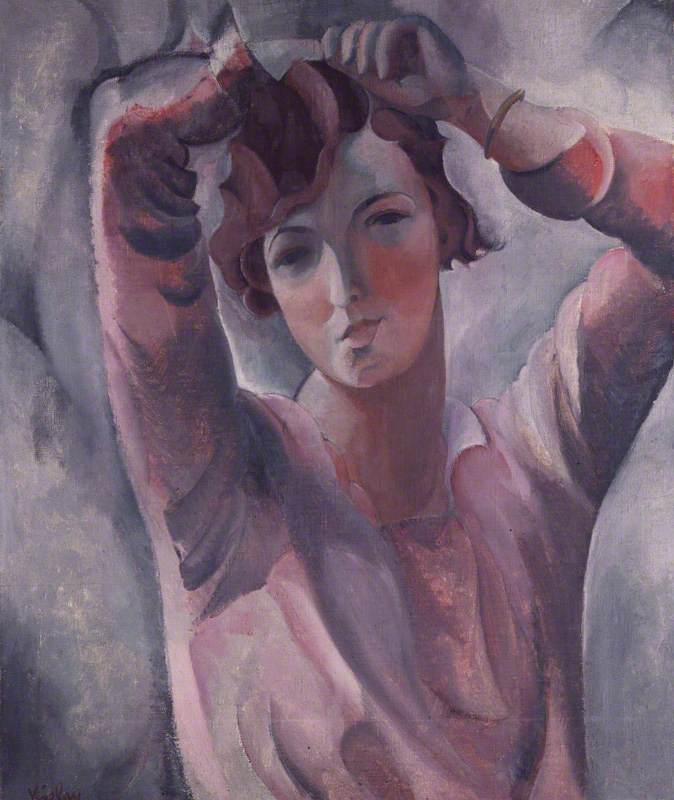

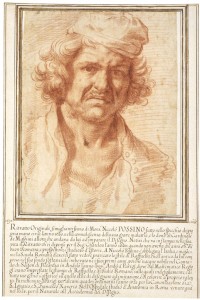

Self Portrait, Holding an Artist's Palette

c.1675

Mary Beale (1633–1699)

Beale sent her Discourse to Tillotson from Allbrook, Hampshire, in the late 1660s, where she and her family had moved to escape the plague. It was at Allbrook that she is likely to have painted her self portrait with palette and canvas now in the National Portrait Gallery, and where Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler (1653) visited her. The farmhouse she lived and painted in survives, though little is currently being done to recognise or preserve its historical importance. It is not known whether the racks for drying canvases, which Mary Beale installed, and which were still in place 300 years later, in the 1950s, still remain. There is no memorial to Beale in St James's Church, Piccadilly, where she was buried, a stone's throw from her studio in Pall Mall.

Alicia Foster, curator