Although I have not done any active research on Castle Howard since I was a postgraduate student at the Warburg Institute in the late 1970s, I still retain a deep interest in it, what new work is being done on it, and particularly enjoy revisiting it, now over forty years since I used to bicycle up the long hill from Welburn on a butcher’s bike to work in the archive.

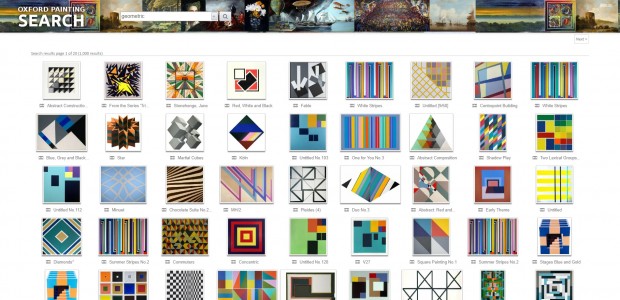

So, when I was asked by Art UK's Director Andy Ellis if there was a country house I would be interested in investigating for the Art UK website, I naturally thought that I would explore whether or not there were any pictures relating to its history which I could locate through Art UK.

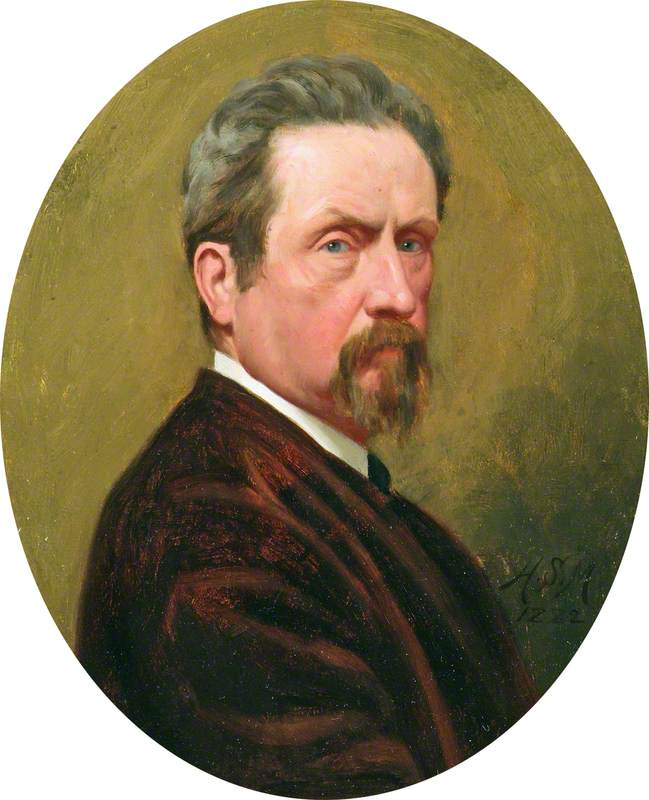

Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle

c.1700–1712

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

There is the Kit-Cat portrait of Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle, who was the subject of my PhD, as the man who commissioned Castle Howard. It is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, one of the

The Art UK website dates the portrait to any time between 1700 and 1712, which is probably a reasonable estimate, since there is no documentary evidence. This was the period when the Earl of Carlisle was most politically active, spent more time in London than in Yorkshire and when the Club itself helped pay for the construction of the Queen’s Theatre in Haymarket. The National Portrait Gallery, on the other hand, dates, it to 1715, thinking that the staff he is shown as carrying may relate to his very brief appointment as first Lord of the Treasury on the accession of George I. I think Art UK is more likely to be right.

Kneller’s portrait of Sir John Vanbrugh belongs to the same series. They were all donated to the National Portrait Gallery by the Art Fund in 1945 and are now split between Beningbrough Hall and Room 9 on the top floor of the National Portrait Gallery.

I had forgotten, but was reminded by the Art UK website, that the National Portrait Gallery owns another portrait of Vanbrugh, later than the Kit-Cat, showing him with a patterned silk waistcoat and wearing the badge of Clarenceux King of Arms, as painted by Thomas Murray, a prolific, but now forgotten Scottish artist, whose self portrait hangs in the Uffizi corridor. There is a third portrait, which I didn’t know about, belonging to the RIBA.

Of the portraits associated with the early history of Castle Howard, the most resonant so far as I’m concerned is the portrait of Sir Thomas Robinson by Frans van der Myn, also in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Thomas Robinson, known to his friends as 'Long Sir Tom' owing to his height, inherited his father’s house at Rokeby in North Yorkshire in 1723. He planned to redesign it, originally to plans drawn up by William Wakefield, but afterwards to plans he himself drew up in spite of the offer of help from Lord Burlington, another of this circle of Yorkshire landowners.

In 1728, he married Lady Elizabeth Lechmere, the widowed eldest daughter of Lord Carlisle, which gave him a privileged position by which to criticise Hawksmoor’s designs for the mausoleum at Castle Howard. Together they embarked on a Grand Tour, travelling to Rome by way of Paris and buying 'most of the good books and plans of

In 1750, after the death of Elizabeth Lechmere, he commissioned a portrait of himself by Frans van der Myn, showing him sitting bolt upright in front of table with three books on it – Palladio’s Quattro Libri in an English translation, the works of Shakespeare and what purports to be the first volume of his wife’s poetry, in spite of the fact that no such volume was ever printed.

I don’t think that any of this information, freely available by dint of browsing on the Art UK website and following the links through to those of the National Portrait Gallery and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, was new to me. But what became clear to me after an afternoon of casual browsing is how quick and easy it is now to assemble this type of biographical and iconographic information whereas, when I was working as a research student, it involved long hours of sitting in the local history section of the Institute of Historical Research, putting together information from ancient printed works of reference and filling out multi-coloured record cards (white for books, yellow for biographical information) for a big card index which I now never use.

I remember at some point during my research a cousin of mine saying that he thought it was ridiculous that postgraduate research should still involve so much travelling to archives and laborious longhand transcription. Towards the end, my supervisor, Michael Baxandall, told me about a friend of his in Berkeley, California who had acquired a machine like a typewriter, but which was able to make automatic corrections. I think that this must have been the first time that I heard about a personal computer.

When I was a Trustee of the Public Catalogue Foundation (the predecessor to Art UK), I still thought it was sensible to produce printed catalogues. I was wrong. I had no idea then what an incredible revolution in research the internet was going to be and I only wish that Art UK and its website had been available when I first embarked on my PhD.

Charles Saumarez Smith is the author of The Building of Castle