Art UK is undertaking a twelve-month scoping project (from 2024 to 2025) to explore adding more ceramics to our platform and telling the story of ceramics in UK collections.

Objects made from clay can already be found on the Art UK website, but these items represent a very small proportion of the hundreds of thousands of ceramic objects in UK museums, galleries and other institutions.

Thanks to generous support from the project funders, The Headley Trust and The French Porcelain Society, we will examine how Art UK can provide a means for people across the world to find and explore ceramics from UK collections. Research is being undertaken to assess the nature and extent of collections' holdings of ceramics in the UK, how the ceramics are documented and how many have been photographed.

We are assessing how Art UK can use the Museum Data Service to bring ceramic objects from UK collections onto Art UK. As well as importing a selection of ceramics onto Art UK as part of this scoping project, we will explore opportunities for future ceramics projects, content and activities, including stories, learning resources and community-based programmes.

This project is being run with the support of the Art UK Ceramics Steering Panel, who have a wide variety of expertise and skills relating to the history, collecting and making of ceramics.

We are delighted to have two new staff members working on this scoping project at Art UK – Gracie Price, Data Officer (Ceramics) and Miranda Goodby, Ceramics Researcher.

To celebrate the start of the project, we have asked Gracie and Miranda to each select three ceramic items from Art UK, to give you a taste of some of the wonderful ceramics you can already see on our website. Here's what they have chosen.

Gracie's chosen ceramics

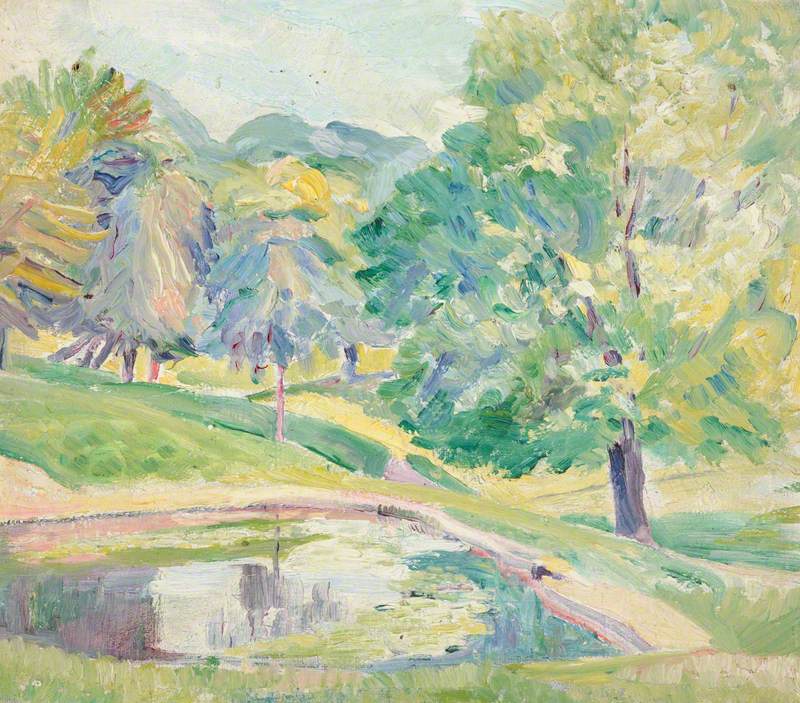

Landscape by Lorna Graves at Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery

The sculptor and painter Lorna Graves was heavily influenced by the landscapes around Cumbria where she settled. It is easy to see the reflections of the prehistoric landscapes within her work.

This assemblage piece is a wonderful example of her carvings, animal forms and designs which reference archaeological material. In this piece Graves has deconstructed the landscape, representing the earth with a labyrinth plaque and the sun in a more literal interpretation. The human head and animal form allude to Cumbria's farming landscape whilst the sky holds a possible goddess figure.

Working in earthenware gave Lorna Graves the potential to low fire her work with the traditional raku method which involves removing the red-hot work from the kiln, placing it in a range of combustible materials. The heat from the clay causes these materials to ignite, creating a smoky reduction environment which gave her work its ancient and earthy appearance. The act of sculpting and carving the work by hand, and the intensive raku firings, were ritualistic processes for Graves. Her simplistic forms are timeless objects which provide gentle reflections of her landscape.

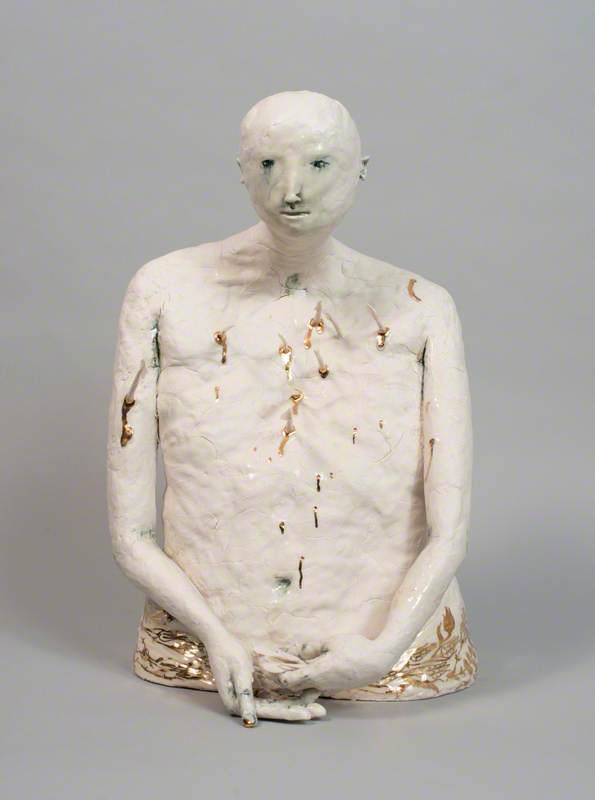

Saint Sebastian by Claire Curneen at Manchester Metropolitan University: Special Collections Museum

Porcelain, a notoriously tricky clay to work with particularly when hand-building, is transformed into something magical by Claire Curneen. Using only hints of oxide and gold, it is the qualities of the clay and the marks left in the making process which bring her works to life.

Curneen's sculptures exist in liminal spaces, at a brief moment when time has stopped. Many of her works explore figures experiencing trauma, seen as both physical and implied trauma. In her recent 'Seven questions' interview, with curator Andrew Renton, Curneen explained that 'you know when somebody's having a tough time, it's fleeting as well. I'm often quoting these grand figures but they're about something quite familiar and close to us that we just walk by.' Her work captures us in those moments, making us look closer, waiting for time to start again and the piece to move on.

I first encountered her work in the ceramic galleries at the V&A. I was mesmerised, viewing her work from as many angles as possible. Getting to see a wider collection of her work in such detail through Art UK holds just the same magic.

Cofiwch Dryweryn / Remember Tryweryn by Emily Jenkins at MOMA MACHYNLLETH

Ceramics can be a very mindful process. With so many techniques to learn it is an evolving medium. Working with clay could alleviate anxiety symptoms and can provide a creative way to process significant personal or wider cultural events, as with the piece Cofiwch Dryweryn / Remember Tryweryn.

This work explores the drowning of the Welsh village Capel Celyn to create a reservoir which now supplies water to Liverpool.

Laid out in the plan of the original village, the work gives a glimpse of the village as it exists now. The village from the houses to the cemetery all still sit below the waterline. With this work artist Emily Jenkins imagines the village within that watery world – look closer and you will see the water that supplies a city and the fish that have a new habitat. Each cottage is stamped with the name of the original cottage it represents.

Miranda's chosen ceramics

Parrot Teapot by Michelle Erickson at The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery

Michelle Erickson is an American ceramic artist who has mastered, and in some cases re-created, historical making techniques to create wholly contemporary pieces, often with a strongly political message. Erickson studied and lives in Virginia, the home of America's first capital, and this led to her fascination with historical ceramics.

Fragments of British, European, Asian and Native American pottery unearthed in early colonial excavations embody a remarkable global convergence of cultures in clay. Michelle's practice is in the rediscovery of lost ceramic techniques and the context of this history defines her approach as a contemporary artist.

This teapot combines many elements of the types of eighteenth-century Staffordshire pottery found in both archaeological excavations and museum collections in Virginia to create something in which every feature is familiar, but which is combined to create something that could never have existed historically.

Fukushima No. 8 by Paul Scott, Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and Galleries

Blue and white printed earthenware decorated with the Willow pattern is often seen as cosy and unthreatening. The unexpected juxtaposition of an image of Hokusai's Great Wave off Kanagawa into that familiar landscape is consequently all the more startling. The wave, which is part of an unrelated ceramic piece, forces itself into the plate, shattering it to pieces, only for the damage to be highlighted in gold using the Japanese practice of kintsugi.

Fukushima No. 8 commemorates the disastrous earthquake of 2011 in which the Tōhoku region of Japan, including the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, was overwhelmed by large tsunami waves, leaving thousands dead and many more homeless.

Paul Scott lives and works near the Sellafield nuclear plant in Cumbria, which he has previously depicted in his printed ceramics. His work invariably deals with contemporary themes, often unexpected, sometimes amusing, frequently challenging and occasionally disturbing.

As Paul Scott says in an interview with Art UK: 'My intention has been to put real landscapes on the plates, to bring attention to the fact that transferware isn't an innocent medium. ... Many people feel that it showed an innocence and purity or whatever, but it's a selective view of the world. I want to rebalance that with some realism.'

Ceramic Plaque by John Piper and Fulham Pottery at Cannon Hall

John Piper is primarily known for his paintings – which often depict landscapes and architectural views, including follies and garden buildings – and for his stained-glass designs, but his ceramics are less well-known. In the 1970s, however, he worked with the potter Geoffrey Eastop to produce a series of plaques with abstract designs or stylised heads, and in 1982, aged 79, he collaborated with Fulham Pottery for the exhibition 'Piper's Pots'.

This collaboration produced over 200 pieces of ceramic, including obelisks, candlesticks, vases and dishes. Among them was a series of 'curly plates', both designed and painted by Piper. Four were decorated with architectural views, taken from a 1767 architectural pattern book by William Wrighte. This one depicts 'A Hermit's Cell' which, according to Wrighte's text, was to be built of large stones and trunks of trees with a thatched roof and a floor of pebbles or cockle shells.

Although it uses the same type of ceramic body – a cream earthenware – the form is reminiscent of Rococo tableware, and it is decorated with an eighteenth-century gothic folly. Piper's 'curly plate' is not a copy, or a reproduction, of eighteenth-century pottery. Instead, it is a re-interpretation of all those elements to produce something entirely of the twentieth century.

Follow Art UK on social media or subscribe to our newsletter to keep up-to-date with Art UK's ceramics project.

Katey Goodwin, Deputy Chief Executive, Gracie Price, Data Officer (Ceramics) and Miranda Goodby, Ceramics Researcher