As a rabbit owner myself, I tend to notice rabbits appearing in paintings on Art UK, here and there: usually innocently adorning a meadow, being squashed by sentimental Victorian children or gruesomely strung up after the hunt. The symbolic meaning of these fluffy creatures can be surprisingly complex.

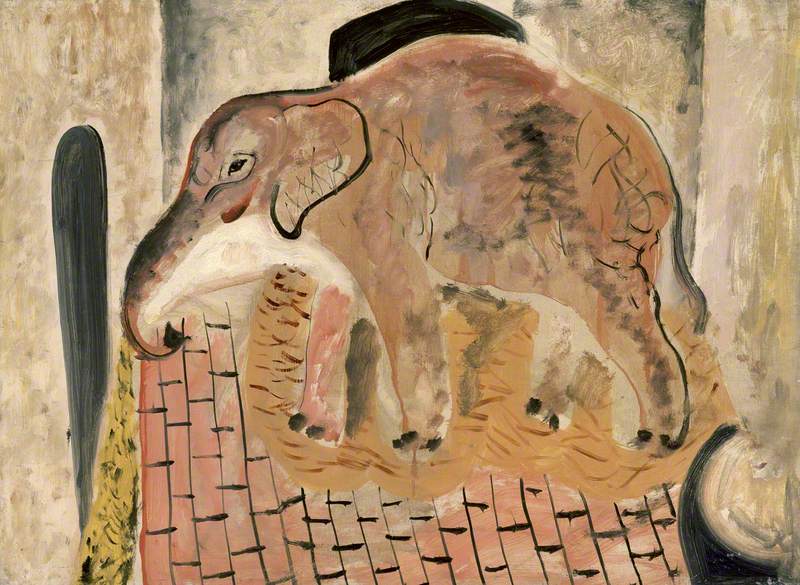

Hares are often associated with birth and resurrection, hence rabbits and hares being a popular symbol for Easter, as well as for modern artists such as Joseph Beuys. They are born, live and die within a short time, in line with the seasons, making them an ideal visual nod to the theme of mortality in art.

Their rapid breeding rate also implies fertility and sensuality, yet as a prey animal, rabbits simultaneously indicate innocence and love: like in this copy after Titian's painting of the Madonna with a rabbit (the original is apparently the earliest known depiction of the creature in art).

Madonna and Child with Saint Catherine and a Rabbit

(recto) (copy after Titian) 1844

Clement Burlison (1815–1899)

In König's Adam and Eve in Paradise an array of non-threatening beasts rest quietly around the couple, who are about to eat the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge.

Two brown rabbits in the foreground almost mirror the figures, nibbling grass; no forbidden knowledge for these two creatures, who get to stay paired up in paradise.

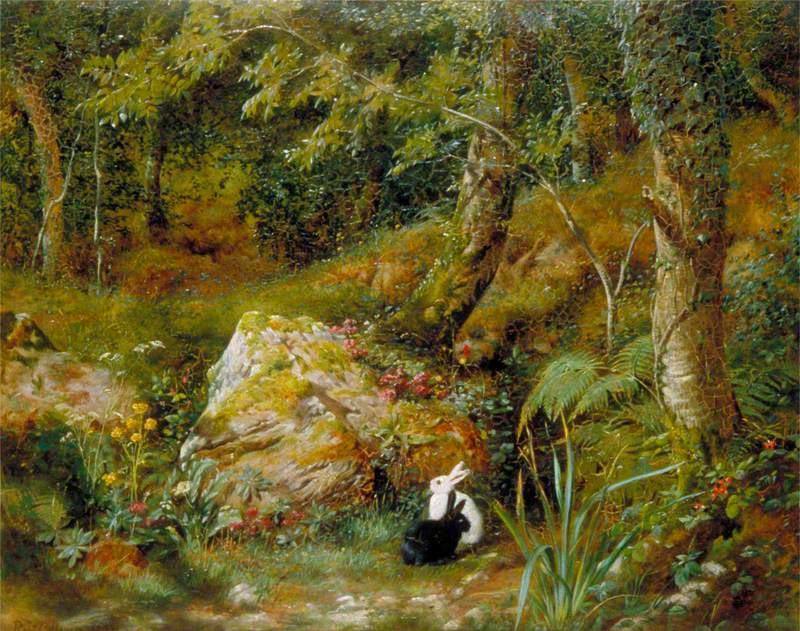

It's interesting to compare this pair of stray rabbits in Robert Collinson's painting to the two in König's work above.

The strays, having been forcibly removed from the wild (the Garden of Eden) and bred by humans (the descendants of Adam and Eve) to produce a somewhat unnatural array of contrasting fur colours. The rabbits then escaped back into the wild, in a strange turn of events.

The ambiguous nature of the rabbit may be traced back to Judaism's attitude towards the mammals. They chew the cud, yet do not have a divided hoof, but were later thought of as a symbol of the Diaspora.

Introduced to the UK from Spain by the Romans, rabbits – due to their fast breeding rate – became firmly established within the ecosystems of the nation, in managed warrens and wild ones dug by rabbit escapees. Apparently favoured by monks (as baby rabbits were not considered true meat, and could be eaten outside of Lent), rabbits' domestication was popularised, and breeds were experimented with to produce different colours of fur. The ability to keep rabbits would mean a fairly consistent source of meat for a struggling family.

Domesticated rabbits were later brought into the cities, firstly for food, but during the nineteenth century rabbits became domesticated for pleasure. The benign, soft and perfectly sized pets became favoured by the Victorians, as eating rabbit meat declined in popularity.

It is rare for a domesticated animal to be both considered food and a treasured pet, yet this is what appears to have happened in popular culture for the rabbit. Rabbits have become at once pedestrian, firmly situated within human domesticity, and also somehow mystical; Beatrix Potter and Lewis Carroll popularised the rabbit as a magical character, with a supernatural ability to talk.

It is a strange contrast to see the rabbit alive and adored in one painting, and as part of a sumptuous feast in another, its dead body a symbol wealth and sensuality. (Though I like this rare example, above, of a living bunny sitting among a lush harvest of vegetables, and the rabbit's almost cheeky expression). The range of rabbits and hares on Art UK tells how conflicted our attitudes are to these creatures: devastatingly, an article from 2006 indicated the RSPCA believed the rabbit to be the 'most abused' pet.

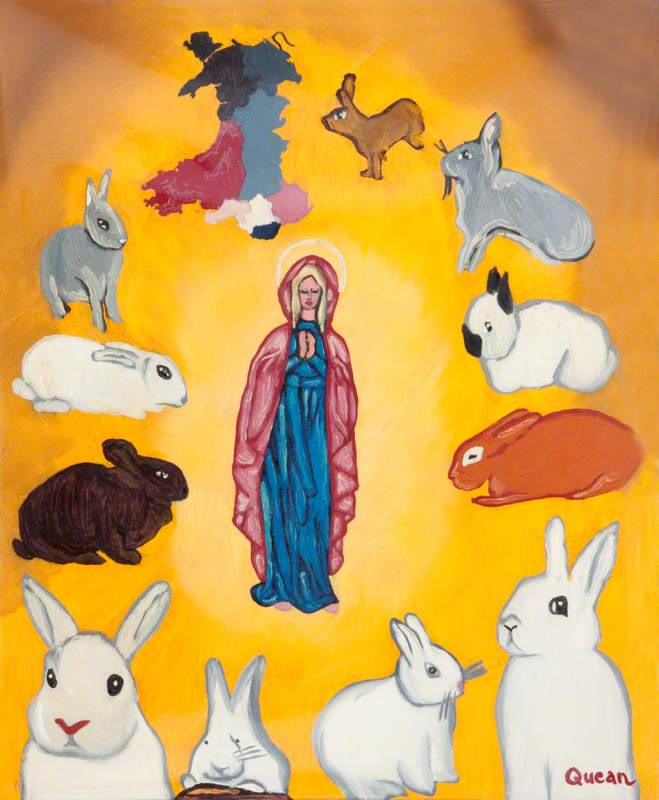

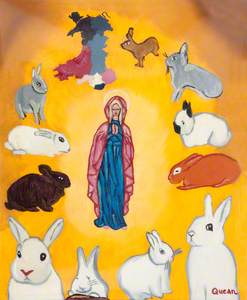

I'm fond of this naïve-style painting of Saint Melangell by Quean Andreassen. Apparently Saint Melangell, an Irish-born hermit, who lived in Wales in the seventh century, sheltered a hunted hare under her robe. The hunter, Brochwel, Prince of Powys, was moved by her courage when facing his hounds and gave her a valley as a place of sanctuary. Saint Melangell remains the patron saint of rabbits, hares and the natural environment.

Jade King, Art UK's Head of Editorial