Content warning: this story contains reference to sexual assault.

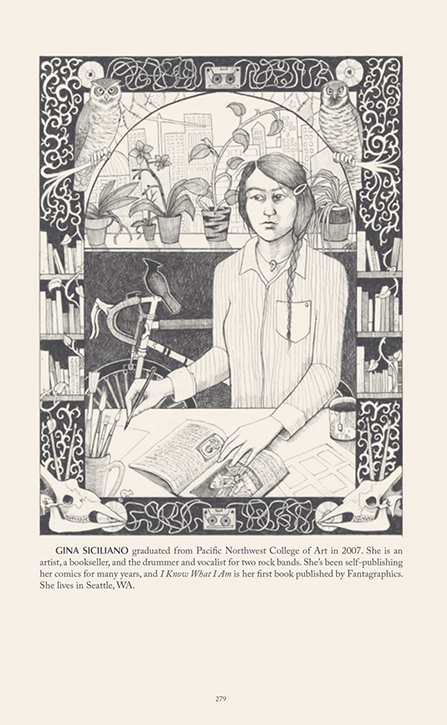

In 2007, the Seattle-based artist Gina Siciliano had a transformative moment when she stood in front of Artemisia Gentileschi's work Judith Beheading Holofernes (c.1620) in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. As beautiful as it is violent, the work's unapologetic expression of female rage – created over four centuries ago – stirred Siciliano into action.

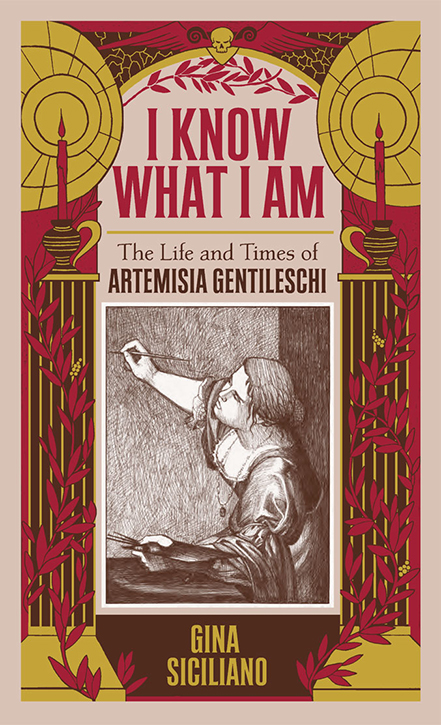

'I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi' by Gina Siciliano

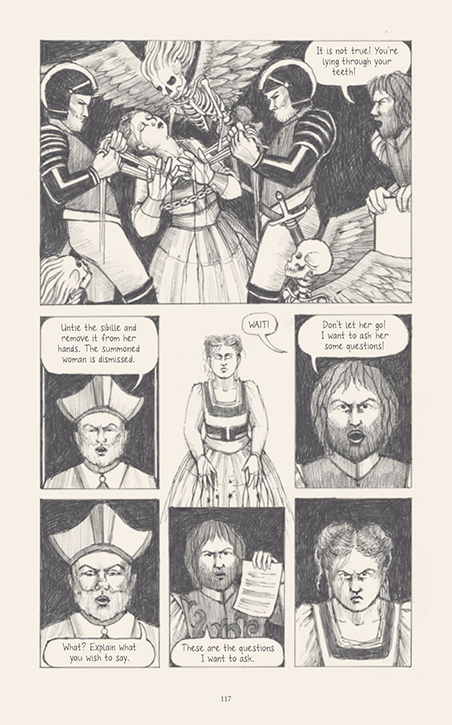

Like the seventeenth-century Baroque master Artemisia Gentileschi, Siciliano is a survivor of sexual assault. Diving into Artemisia's world, Siciliano spent seven years researching the artist, which culminated in the creation of a graphic novel, I Know What I Am. This beautifully illustrated book contextualises Artemisia's life and includes details about her infamous rape trial in Rome in 1612 – a historic moment that resonates powerfully in today's age of #MeToo.

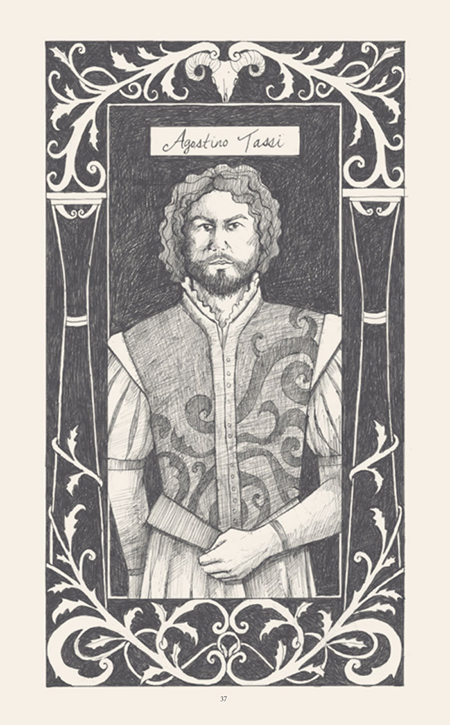

Narrating in unprecedented detail the unfolding events of Artemisia's life, it chronicles her childhood, sexual assault, public trial (which included torture), complex relationship with her rapist, the painter Agostino Tassi, and her tremendous artistic success in seventeenth-century Italy.

Crucially, I Know What I Am avoids the trap of focusing only on Artemisia's shocking life events and downplaying her exceptional artistry. Rather, it brings into sharp focus Artemisia's role as one of the greatest painters of Baroque Italy, who navigated her way through an extremely patriarchal world in which the dogmas of the Counter-Reformation Catholic Church prevailed.

I spoke with Siciliano to discuss the making of I Know What I Am and the life of Artemisia.

Giuditta che decapita Oloferne (Judith Beheading Holofernes)

1614–1620, oil on canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653 or after)

Lydia Figes: What were your initial reactions to seeing Artemisia's Judith Beheading Holofernes?

Gina Siciliano: When I saw Artemisia's painting, I knew immediately that there's nothing else like it. Even Caravaggio's Judith Beheading Holofernes doesn't have the same power or resonance as Gentileschi's.

Whereas in Caravaggio's Judith a squeamish young woman is painted as if holding a stage prop, Artemisia's painting shows two women really committing the act of murder with a sense of vengeance. The logistics of murder are thought out so convincingly.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

c.1598–1599, oil on canvas by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610)

Lydia: Were her contemporaries familiar with this subject matter?

Gina: Judith and Holofernes was a common theme for that time period. Artists and institutions appropriated the story for their own needs. Judith was a heroine of the Catholic Church and she became a symbol of the Church clamping down on heresy during the Counter-Reformation years. Around the same time, Judith was co-opted by the Protestants, who used her as a symbol for their message. Judith was a metaphor for the weak overcoming the strong.

Lydia: What else made Artemisia's work unique in comparison to other versions?

Gina: Artemisia created a radically new interpretation of the theme. Most painters would show the servant Abra as an old hag in the background, looking over Judith's shoulder – whereas Artemisia (and her father Orazio too) painted a younger Abra helping Judith. The painting shows female solidarity; two women working in unison.

But there is also a deeper symbolism within Artemisia's Judith Slaying Holofernes: one which is potentially autobiographical. The question as to whether Artemisia painted herself as the figure of Judith has been riveting art historians for decades. Is that Agostino Tassi getting his head cut off? And is this a revenge painting by a woman seeking a cathartic release, painting herself and her attacker into the painting?

Jael and Sisera

1620, oil on canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after)

Lydia: When did debates about the autobiographical element of Artemisia's work first emerge?

Gina: In the 1980s, Mary Garrard was the first to write a comprehensive monograph on Artemisia in Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art (1989). This book transcribed and translated the details of Artemisia's trial. Garrard argued that Artemisia's perspective as a woman painter and survivor was different from her male contemporaries, and that there was a protofeminist undercurrent to her work.

However, there was a backlash against Garrard's feminist interpretation, with many scholars claiming that we don't have substantial evidence to prove that these females really were Artemisia. In one of her letters, she mentioned hiring female models, so we know she didn't always use herself, especially when she had her own workshop set up.

Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria

c.1615–1617

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after)

Interestingly, people are now returning to Garrard's feminist reading of Artemisia, and discussing the potential for autobiography within the paintings. For an artist to paint themselves into their work was not uncommon. A lot of Artemisia's contemporaries would paint cryptic messages into their work – sometimes portraying their rivals or enemies, or painting themselves in. It wasn't unheard of for real life to enter these works of art.

Personally, I think she was painting herself sometimes, or even a lot of the time. As a painter, I paint myself too – I'm a free model!

Lydia: On top of this, if Artemisia was initially barred from academic training wouldn't it be plausible that she'd use herself as a model?

Gina: Yes it is plausible. As a young woman, Artemisia wasn't allowed entry to the prestigious academies (though she eventually became the first woman to be elected into the Florentine Accademia di Arte del Disegno). After the Counter-Reformation in the sixteenth century, the Catholic Church created strict guidelines for what could and couldn't be painted. The female body was taboo – but unlike her male contemporaries, Artemisia could paint her own reflection.

In part, Artemisia's fame at that time relied on the fact that she was able to paint the female figure in a novel way. A lot of her patrons commissioned her to paint seductive female figures.

Danaë

c.1612, oil on copper by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after), previously attributed to Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639)

Lydia: Besides presenting Artemisia's artistic talent, your book considers the relationship between her painting and personal life. In particular her complicated feelings toward her abuser Tassi, who was eventually found guilty of rape after an eight-month trial in 1612 and banished from Rome. What can we take away from Artemisia's experience?

Gina: So much has changed since Artemisia's time, but in some ways very little has changed. It seems as if survivors are still facing the same judgements, the same doubts, the same questions from authorities. Sexual assault doesn't look like what people think it looks like – it's not black and white.

For a long time, feminists have been working to change the ideas people have about sexual assault, and this is where Artemisia's story becomes particularly relevant in today's ongoing discussions. For example, in reality, assault is usually committed by someone the woman already knows, often by men who are talented, or powerful. We don't want to believe that our heroes are capable of committing these horrible things, but they are.

In Artemisia's case, her rapist was celebrated painter Agostino Tassi, who had worked with her father and was closely acquainted with the Gentileschi family. When Tassi refused to marry Artemisia after forcibly taking her virginity, her reputation (as well as her father's) was tarnished considerably. This led Orazio to initiate the trial – not Artemisia. Since chastity was the foundation upon which a girl's honour was built, her sexuality was basically a liability.

The rape not only dishonoured Artemisia and her family, but it also hindered her prospects within the marriage market. Therefore, the rapist, Tassi, was expected to repair the damage by either marrying Artemisia or providing dowry money.

Agostino Tassi in 'I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi' by Gina Siciliano

For Artemisia, there may well have been a part of her that loved Tassi or loved his work. She may have sincerely hoped that he would marry her – this is all possible. Nevertheless, she refused to absolve Tassi of the crime during the rape trial.

Trial scene in 'I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi' by Gina Siciliano

Lydia: Can we regard Artemisia as a precursor to modern feminism?

Gina: There was no political push for women's rights during Artemisia's era. But when you start digging deeper and looking more closely at the history, there was, in fact, something we could call 'protofeminism', which refers to an earlier version of the kind of feminism we know today.

While many scholars and historians claimed that there was no feminism during Artemisia's time – because there was no political movement – others have shown that in some circles there was an ongoing intellectual debate about the roles of women.

For example, Jesse Locker's book Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting refers to this idea of 'protofeminism' during Artemisia's time, in which new debates about the role and nature of women were ignited. These discussions were particularly prominent in France, but also in Italy.

Arcangela Tarabotti (1604–1652) was a Venetian nun and writer whom many have regarded as a protofeminist writer. There was also Lucrezia Marinelli (1571–1653), a defender of women's rights who published The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men in 1600. However not all of Marinelli's writing was super feminist; it was Tarabotti who was more consistently outspoken about women's rights. It is also possible that she knew Artemisia. I think Artemisia was certainly attuned to the protofeminist thought of her time.

Lydia: To what extent did other women propel Artemisia's career as an artist?

Gina: Although there were important female patrons at that time, it appears that Artemisia had more male patrons than female.

After Cosimo II de' Medici died, the two women regents – Christine of Lorraine and Maria Magdalena of Austria – became official rulers of Tuscany. They commissioned many female artists and composers, however they didn't appear to be interested in Artemisia's work.

Lydia: Lastly, what is your favourite Artemisia painting?

Gina: That's so hard to answer, though I'd have to say Artemisia's Judith Beheading Holofernes.

Self-portrait by Gina Siciliano

Gina Siciliano's I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi is published by Fantagraphics.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK