When you take a sip of wine, the context matters: the accompanying food, season, and atmosphere all affect what your palate perceives. In the same way, wine's meaning has changed based on the place and period in which it has been shared and consumed.

Wine has featured in myriad artworks throughout history, from ancient murals of bacchanals to medieval harvest tapestries, Renaissance feast scenes to modern still lifes. Over the centuries and across cultures, wine has been used as a visual signifier of taste, class, courtship and the divine. Its varied depictions reveal its varying cultural significance.

Divine connection

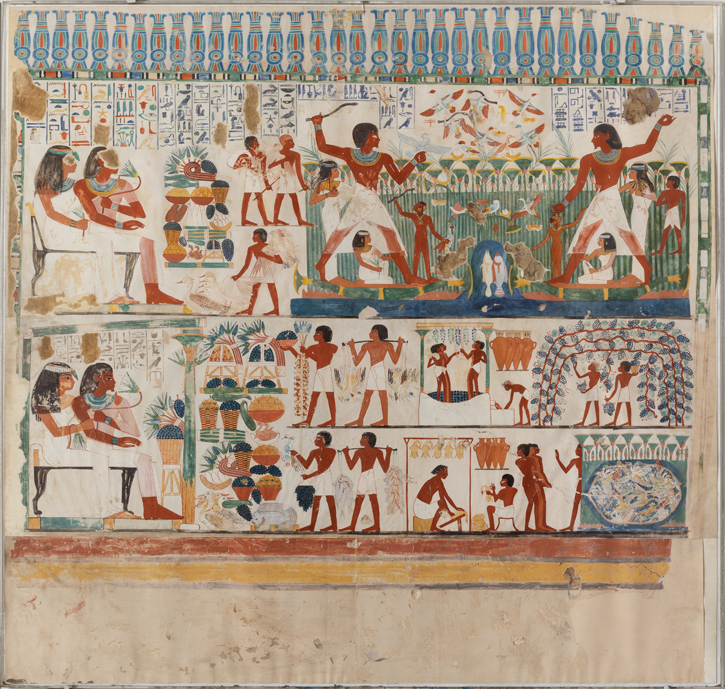

While beer was an everyday drink in ancient Egypt, wine was more often reserved for gods and funerary rituals, in part because it was thought that intoxication could facilitate communion across the barrier between life and death. Some of the earliest depictions of wine showed both the process of its creation and its offering to the gods to facilitate the promise of an enjoyable afterlife.

A wall painting in the tomb of a court official from the 18th Dynasty (c.1550–1292 BC) depicts the process of Egyptian winemaking, with grapes being picked from trellises, processed and stored in amphorae. The scene was part of a larger series depicting fishing and hunting to promote the continuance of these activities – and their plentiful results – in the afterlife.

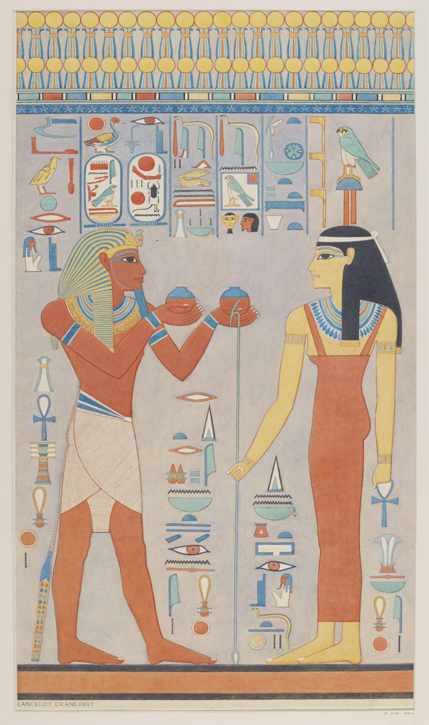

Another illustration from the tomb of King Haremhab shows the ruler offering two vessels of wine to Hathor, a fertility goddess who was celebrated with a festival of ritual drinking.

Osiris, god of the underworld and agriculture, was frequently offered wine in religious practices and images as well.

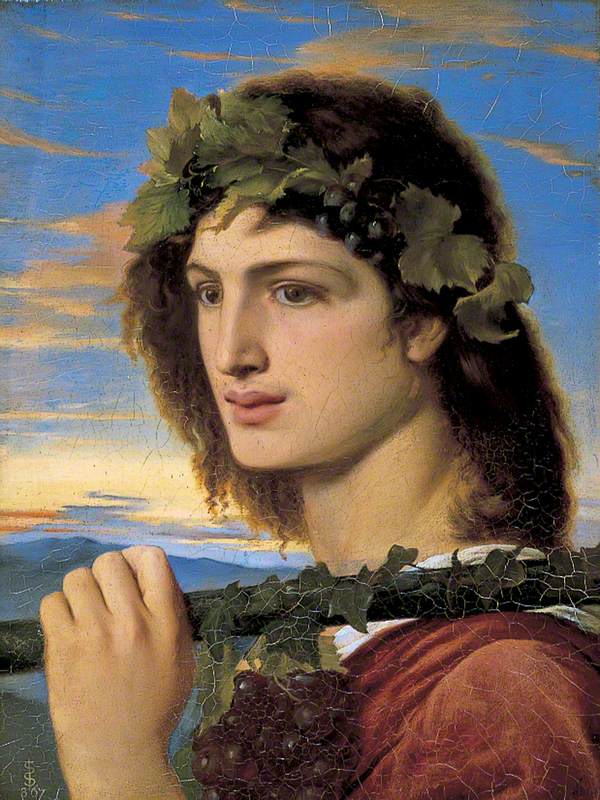

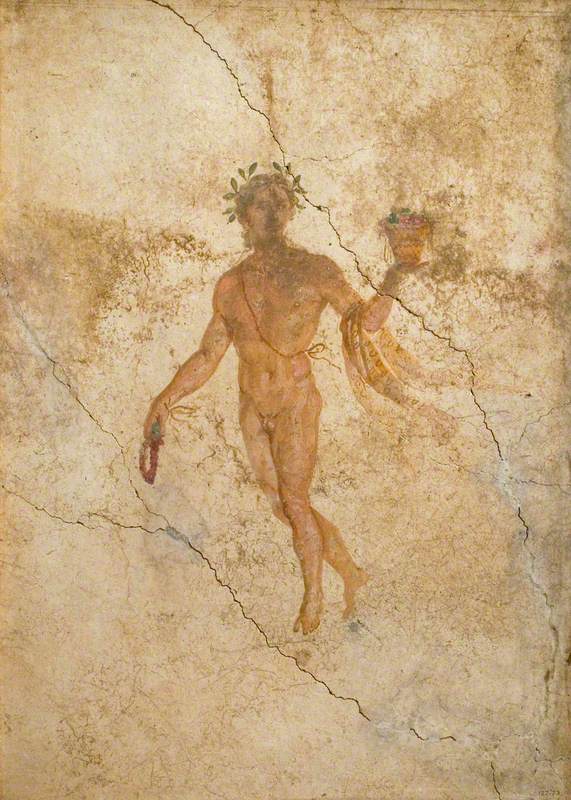

The close ties between wine, fertility and harvest also appeared in the patronage of Greek and Roman gods.

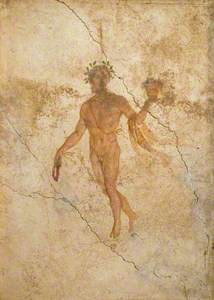

Dionysus, known as Bacchus by the Romans, was celebrated with drunken festivals (bacchanalia) that featured ecstatic dance and later became a byword for hedonism. Frequently depicted nude or semi-nude and crowned with a grapevine wreath, Bacchus also appears in many scenes of bacchanals accompanied by frolicking followers. While tied to freedom from many societal strictures, Bacchanalian intoxication was meant to inspire divine joy and liberation from cares, as distinct from wasteful drunkenness.

Drunken Silenus supported by Satyrs

about 1620

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) (attributed to)

Silenus, a minor god of winemaking and drunkenness, who was tutor and companion to Dionysus, also appears in numerous contemporary and later depictions. The Renaissance and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Neoclassical revival saw a resurgence of interest in classical gods and interpretations of their ribald shenanigans, which tended to reflect indulgent hedonism rather than religious significance.

Blood and sacrifice

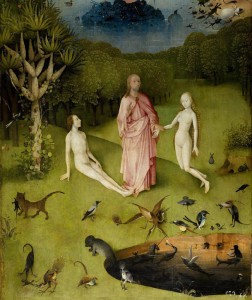

In the Christian tradition, wine is inextricably linked with stories of Jesus Christ during his time on earth. But unlike the intoxicated communion of earlier faiths, wine's power became associated with miraculous, symbolic sacrifice.

Christ was said to have turned water into wine at a wedding feast at Cana, which was among the events depicted in narrative cycles of his life, like in the seventeenth-century alabaster carving above, and this painting by Murillo.

The Marriage Feast at Cana

c.1672

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682)

Another key moment, the Last Supper, recurred frequently in European art from the Middle Ages onward. The scene features the wine that Christ commanded his followers to drink shortly before his death, in memory of his sacrifice.

A painting by the studio of Juan de Flandes shows the apostles gathered around the standing Christ, who holds the bread that symbolises his body near a large, central chalice of wine, symbolic of his blood.

An even more literal depiction of the Christian connection between blood and wine is found in Francesco Granacci's altarpiece painting of Christ the Redeemer.

Christ the Redeemer

early 16th C

Francesco Granacci (1469–1543)

The crucified Christ's blood pours from the wound in his side into a communion chalice, underscoring the Catholic concept of transubstantiation – that the consecrated wine is actually divine – and reminding viewers that this sacrifice was intended to redeem humanity from their sins.

Fruits of the harvest

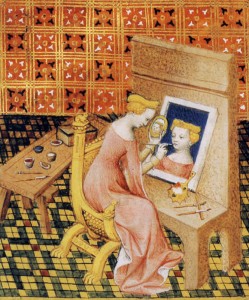

While linked with the divine, wine remains an earthly substance, grown from the soil and tended by humans. As such, depictions of viticulture began to appear in calendar cycles of manuscripts and tapestries in the Middle Ages to show seasonal activities, including a lively, lavish Netherlandish tapestry that depicts peasants labouring through the stages of winemaking and the aristocracy observing their efforts.

Les Vendanges / The Grape Harvest

early sixteenth century, tapestry by Southern Netherlandish School

Cloistered religious orders frequently cultivated vineyards and brewed beer as part of the monastic practice of 'ora et labora', the combination of regimented prayer and work.

Because of this, depictions of winemaking were often found in illuminated manuscripts, including a handbook on health that shows a man stirring a vat of grapes and a monk tasting the output from a wine barrel in illuminated capitals (see f.44–45). These kinds of depictions also appeared on wall frescos and stained glass windows, linking the harvest to the righteousness of hard work – or playfully indicating when participants were enjoying the fruits of their labour a bit too much.

Sogdian Banqueters

early eighth century, wall painting in Panjikent, Tajikistan (site XVI:10)

The fruits of the harvest were also celebrated in numerous feast scenes across cultures, including scenes of banqueting in Sogdian wall paintings in what is now Tajikistan.

Sipping seduction

Through the seventeenth century, depictions of wine continued to appear as both celebration and sacrament. Wine also came to be used as a shorthand for moral or erotic symbolism, through images that either revelled in or chastised the effects of the drink.

In the seventeenth century Dutch Golden Age, popular genre paintings could lean either way – or remain ambiguous in their meaning. A painting by Gabriel Metsu – of a gentleman bowing and offering a wine glass to a lady at a spinet – shows a courtly seduction scene, though the outcome remains uncertain (as indicated by the dog in the corner still sizing the suitor up).

Interior with a Lady at a Spinet and a Gentleman Offering Her a Glass of Wine

c.1667

Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667)

Another painting of a woman pouring wine for a man has a clearer message: the older woman in the background is most likely a procuress, who would coordinate payment for a sexual encounter. As wine was considered an aphrodisiac, it played a pivotal role in the action of both scenes.

Though these images were popular for their subtle erotic content, boisterous, red-faced drunkenness was frowned upon in Dutch society.

Jan Steen was one of many artists who used humorous moralising to poke fun at those who took their drinking too far in paintings like The Dissolute Household and The Effects of Intemperance.

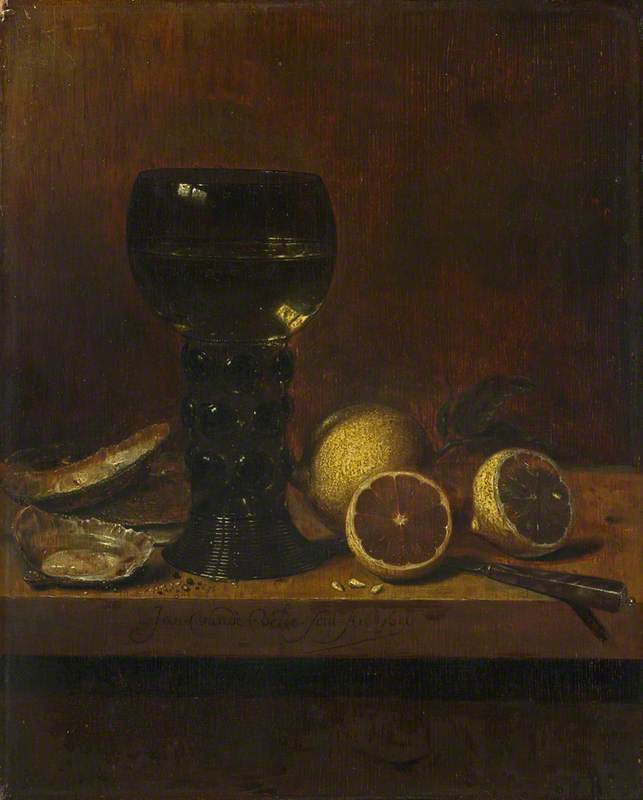

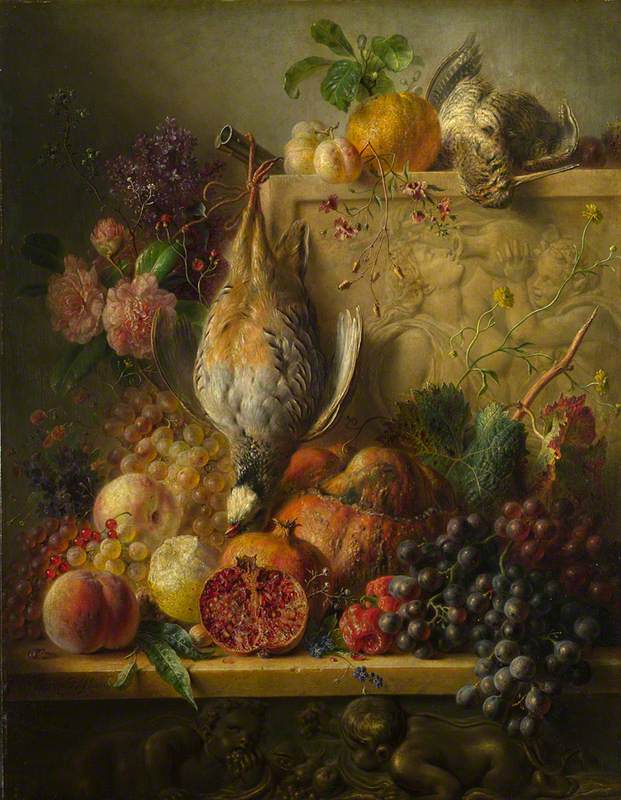

In still lifes of the period, wine often became a tool to showcase an artist's skill at depicting light and reflection as well. However, it was also part of these paintings' underlying message that all earthly pleasures are fleeting, and all beauty will eventually decay.

Fruit Piece with Wine Glass

1692

Barend van der Meer (1659–1702)

Still, sensual pleasures – and depictions of them – remained popular in many places. In Iran during the Qajar dynasty of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, decorative images, like this painting of a woman pouring wine, were common.

Taken from the palace of Fath 'Ali Shah (reigned 1797–1834), it may be an imagined portrait of a member of the royal harem.

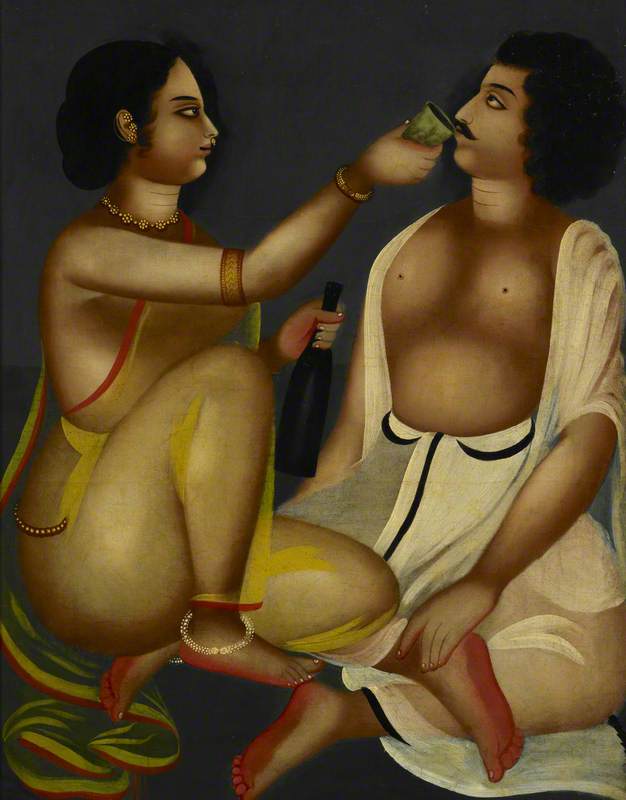

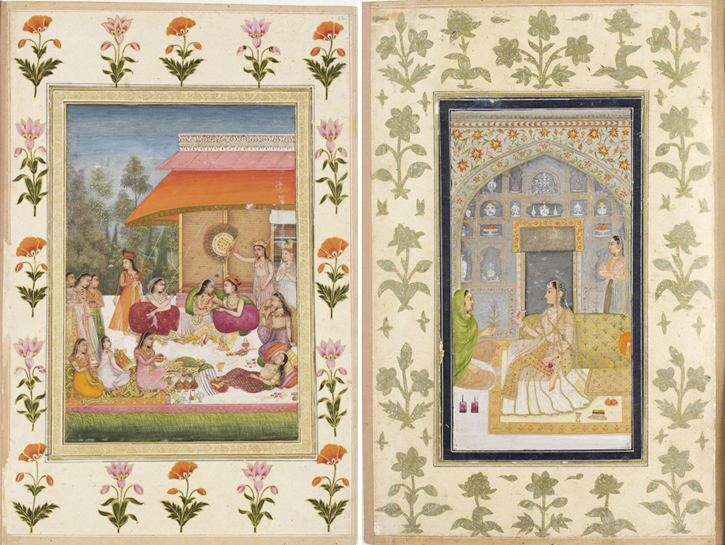

Late eighteenth-century Mughal miniatures from India also show scenes of wine-soaked feasting and beautiful women carrying wine – though technically forbidden in Islam, the rules were different for the ruling class.

Ladies Feasting and Drinking Wine and Lady in Pavilion (Small Clive Album)

early eighteenth century, opaque watercolour & gold on paper by unknown Mughal artist

Another Indian painting from the period depicts a woman offering wine to her lover, again underscoring the ties between wine and desire.

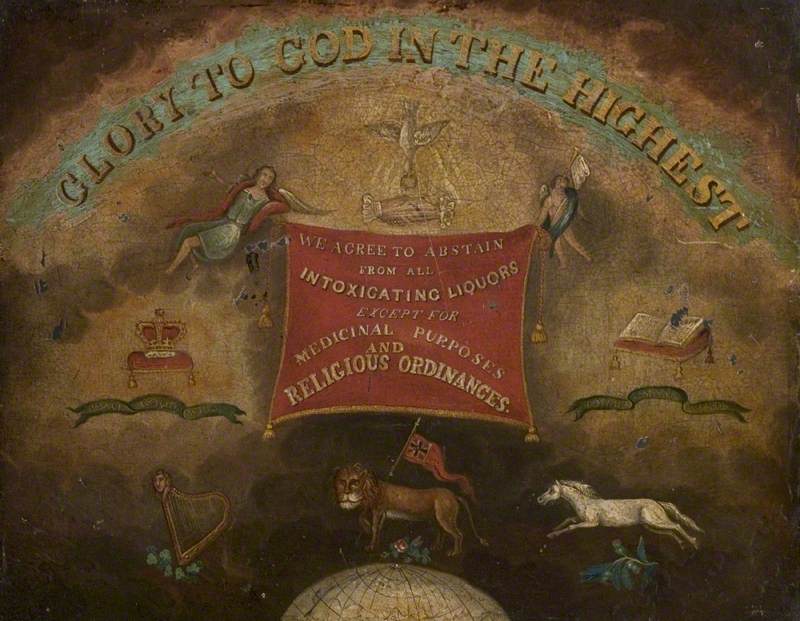

Secular wine

While the effects of wine – for good and ill – were generally understood, the rise of the field of medicine during the Enlightenment brought new opportunities to caricature the tensions between new and old forms of 'tonics'.

In a quasi-Dickensian contrast, The Effects of Medicine and Wine Drinking Compared portrays a reedy, devil-besieged man who takes medicine as far less jolly than the corpulent man surrounded by bottles of wine.

With the rapid cultural changes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came further depictions of secular disillusion and dissolution through wine, as in Manet's famous work A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

1882

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

The scene shows model Suzon standing between bottles of wine, disaffected and removed from the bustling bar, although the version of her reflected in the mirror appears to lean toward a customer, hinting at the divide between internal life and the demands of a job in service.

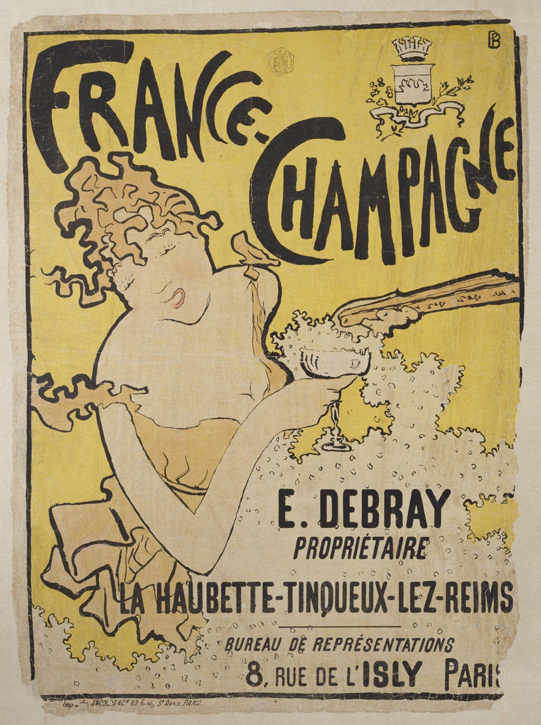

Though Manet's painting took a cold, realist attitude, other artists were enlisted around the same time to create upbeat advertisements for wine, like Pierre Bonnard's frothy, curvilinear France-Champagne advert.

France-Champagne

1891, colour lithograph by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947)

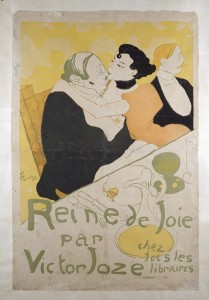

With lithography making mass printing possible, the foundations of modern advertising were laid, and would lead to a proliferation of images that attempted to entice customers by linking wine and feminine seduction – from Alphonse Mucha's dramatic turn-of-the-century Champagne Ruinart poster to Taittinger's glamorous revival of the illustrated form in the 1990s.

However, in private portrayals, wine's depressant qualities could be more apparent. The dejection of a woman slumped over a glass and bottle of wine in a c.1949 portrait is conveyed by the dour, green-tinged colour palette along with her pose.

Woman with Glass of Wine

c.1949

Zygmunt Bukowski (1923–2006)

Wine continues to feature in art, and art has increasingly ventured into wine since the evolution of printing technology and visual branding. Many winemakers now collaborate with artists on wine labels, including the Chateau Mouton Rothschild, whose series began in the early twentieth century and has included works by artists such as Picasso, Miro, and Prince Charles.

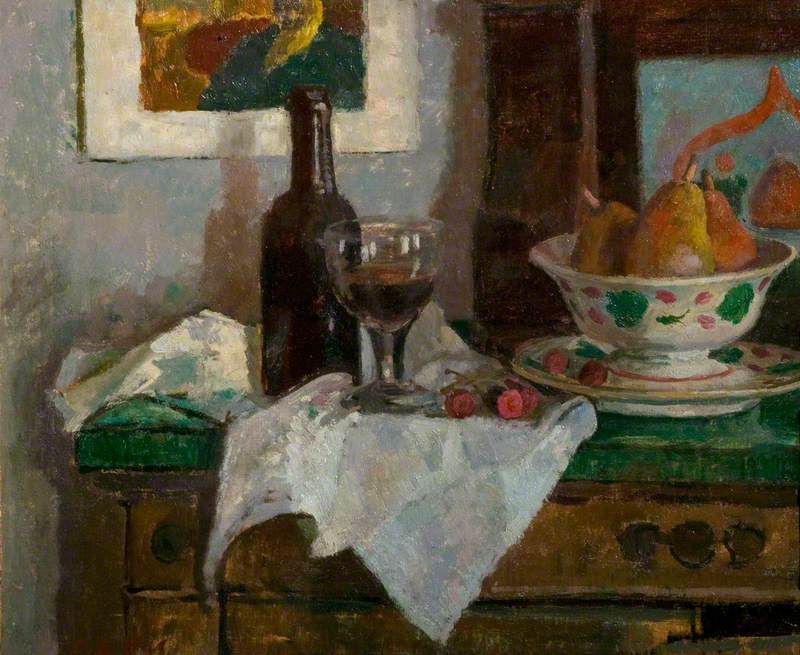

Modern still lifes still incorporate wine as well, although more often for compositional interest than moral intent. With a deeper and broader understanding of wine, its cultural impact, and effects, contemporary depictions of wine can be far-ranging as well.

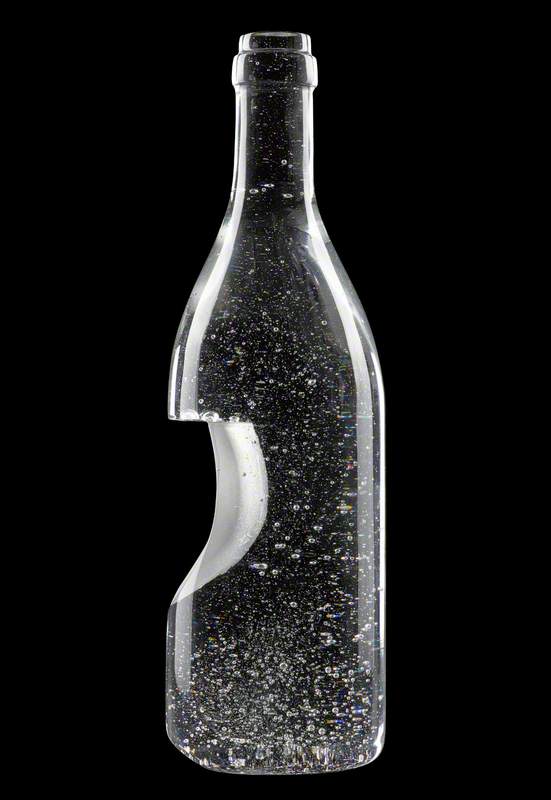

One recent work, Koichiro Yamamoto's glass sculpture Bottle with Wine Glass Cavity, plays with negative space to show the infinite possibilities of wine in our current era, and the evolving shapes it may take in the future.

Anne Wallentine, writer, editor and art historian

Further reading

Betty Hensellek, 'Banqueting in Sogdiana', The Sogdians: Influencers on the Silk Roads, The Freer Sackler, Smithsonian Institution, accessed 2021

Lucia Henderson, 'Blood, Water, Vomit, and Wine: Pulque in Maya and Aztec Belief', Mesoamerican Voices, 2, 2008, pp.53–76

M. Khare, 'The Wine-Cup in Mughal Court Culture – From Hedonism to Kingship', The Medieval History Journal, 2005, pp.143–188

Rod Phillips, Alcohol: A History, University of North Carolina Press, 2014

Rod Phillips, French Wine: A History, University of California Press, 2016

Emily Teeter, Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, 2011