We are used to the stereotypes associated with Brazil and its connotations of tropical fruits, football and sunbathing on Copacabana beach. While these do have their rightful place in Brazilian culture, there remains plenty more to be discovered and appreciated, especially within the country’s rich history of art.

The Embassy of Brazil in London is currently showing 'The Art of Diplomacy: Brazilian Modernism Painted for War' until Friday 22nd June, an exhibition that commemorates the contribution of over 70 Brazilian artists to the British war effort during the Second World War. Originally held at the Royal Academy of Arts, the exhibition welcomed around 100,000 people before touring to seven more locations around the UK. The works are now on loan from public collections in Britain, yet it would seem little is known about the artists behind them. The five artists I discuss below have all helped to define Brazilian art in their own ways and through their generosity began a dialogue between Britain and Brazil that continues to this day.

Lasar Segall (1891–1957)

Although widely celebrated as one of Brazil’s foremost Modernist artists, Lasar Segall studied art in both Germany and his native Lithuania, which was then part of the Russian empire, before emigrating to São Paulo in 1912. His experiences in Berlin and Dresden were key in shaping his artistic style and introducing Segall to German Expressionism and Cubism. During a visit to Dresden in 1914, Segall founded Dresdner Sezession Gruppe 1919 alongside Otto Dix, Conrad Felixmüller and Otto Lange.

Mixing in such avant-garde circles not only liberated Segall from his academic training and Jewish upbringing, but they helped instigate his unique blend of South American influences and Expressionism after returning to Brazil in 1924. Mário de Andrade, a leading figure in Brazilian Modernism, described Segall’s renewed approach as 'a more real concept of reality, abandoning that mortifying and incessant tragedy that characterizes all his work prior to the Brazilian phase.'

As fascism began to spread around both Germany and Brazil, Segall’s works began to reflect more on themes of suffering, persecution and emigration. One of his most famous artworks, Ship of Emigrants, was completed just as Europe was adjusting to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 and 1940.

The earthy tones of his palette add a solemnity to the bodies cramped together and convey the harsh reality for those seeking a better life, presumably in South America.

Emiliano di Cavalcanti (1897–1976)

Emiliano Augusto Cavalcanti de Albuquerque Melo, better known as Di Cavalcanti, was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1897. Di Cavalcanti is widely considered one of Brazil’s finest artists, particularly during the early to mid-twentieth century. São Paulo’s Municipal Theater hosted Modern Art Week (Semana de Arte Moderna in Portuguese) in February 1922, an arts festival involving exhibitions, poetry readings, lectures and concerts. The year 1922 is considered pivotal for Brazilian Modernism and Di Cavalcanti was right at the heart of it, mixing with avant-garde creatives such as Tarsila do Amaral, Victor Brecheret and Mário de Andrade.

Di Cavalcanti spent some years in Paris during the 1920s where he would meet Picasso, Matisse and Braque. Many Brazilian artists from this period sought to fight against European influences, but that did not mean they were against approaching techniques associated with Expressionism and Symbolism from a distinctively Brazilian perspective. Once back in Brazil, Di Cavalcanti dedicated himself to portraying faithful representations of Brazilians from young women about town to the favelas. This also manifested itself in deeply nationalistic beliefs and membership of the Communist Party. While Di Cavalcanti’s works, alongside those of Segall’s and Portinari’s are not overtly political, they are all emblematic of Brazilian Modernism’s mission to establish itself independently from European movements.

Milton Dacosta (1915–1988)

Milton Rodrigues da Costa, more commonly known as Milton Dacosta, was born in 1915 on the Brazilian coast. Dacosta attended the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, not far from where he grew up, until the university closed down due to the 1930 Revolution. In reaction to this closure, a group of artists including Dacosta created Núcleo Bernardelli. Their emphasis was on freedom of artistic expression as well as a place for meeting, discussion and support of the arts.

Dacosta’s reputation began to grow and it was not long before he was studying at the Art Students League of New York and subsequently travelling to Paris and Lisbon. Just as Segall and Di Cavalcanti mingled with the likes of Picasso and Braque, so too did Dacosta. Looking through his oeuvre, it’s clear to see that Dacosta’s travels led to a variety of techniques being used within his painting, such as those associated with Cubism and Metaphysical art. Elements of abstraction, geometry and graphic design are particularly prevalent in the style he developed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Figurative painting, concentrating on the Venus, would dominate the rest of his career until his death in 1988.

Cândido Portinari (1903–1962)

The child of Italian immigrants, Cândido Portinari grew up on a coffee plantation in the state of São Paulo. This was a modest, if not frugal, upbringing which would go on to make an impression throughout the whole of his artistic career. At age 15, Portinari moved to Rio de Janeiro to attend the National School of Fine Arts, where he would develop his talents and win the European Travel Prize to Paris. Like his contemporaries, Portinari missed Brazil and its landscapes, people and culture. Antonio Callado, a Brazilian journalist and writer said that Portinari’s work was a 'monumental book of art that teaches Brazilians to love their homeland more.'

Upon his return, Portinari’s work began to focus more on themes surrounding Brazil’s complicated history of slavery and imperialism, weaving in depictions of the country’s workers and their experiences of poverty. Rather than dwell on their plight, Portinari painted his subjects as humans who experienced as much joy playing games or enjoying a night at the circus as they experienced the tragedy of inequity. Portinari is believed to have said: 'I am a son of the red earth. I decided to paint the Brazilian reality, naked and crude as it is.'

His passion for the Brazilian people would lead to political activism and membership of the Communist Party alongside Di Cavalcanti. In 1956, Portinari donated two murals to the United Nations Headquarters entitled War and Peace, however he was denied access to the US due to his affiliations with the Communist Party and unable to inaugurate the paintings. The murals, 14 meters in height and 10 meters in width, can still be seen at the UN Headquarters in New York City.

Lucy Citti Ferreira (1911–2008)

Lucy Citti Ferreira may have been born in São Paulo in 1911, but she spent large parts of her childhood and adolescence with family in France and Italy, where her artistic talents would begin to flourish. Ferreira first started to develop her skills under the tutelage of André Chapuy at the École Supérieure d'Art et Design in Le Havre. Over the following years, Ferreira studied in Paris and exhibited at both the Grand Palais and the Salon

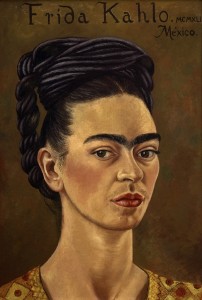

Menina e gatto (Girl with a Cat)

1943

Lucy Citti Ferreira (1911–2008)

After returning to Brazil in 1935, Mário de Andrade is struck by the similarities between the themes and palette of Ferreira’s work and that of Lasar Segall’s. Following Andrade’s introduction, she becomes Segall’s muse and student for over 10 years, being the Lucy depicted in his painting, Lucy with Flower. Despite her associations with Segall and other prominent figures within Modernism, Ferreira’s work was largely overlooked in Brazil. This did not deter Ferreira from painting throughout her lifetime, but I think this is a great shame as Ferreira’s work has a distinct style that sensitively captures the rhythms of quotidian life.

Around 60 of Ferreira’s works were part of a retrospective at the Pinacoteca in São Paulo in 2013 which aimed to re-evaluate her career as separate from her relationship to Segall and draw light to the nuances of her own style.

Victoria Rodrigues O’Donnell, Museum Assistant at the Fashion and Textile Museum and freelance writer