Download and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

July 2019 marked 50 years since man first took steps on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. After two years of research in the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union, Neil Armstrong planted a flag on the area known as the Sea of Tranquility. It's a moment in our collective history where mankind's ingenuity, determination and bravery enabled us to achieve something greater than ourselves.

Long before the Eagle lunar module touched down on the moon, and indeed before man really understood what the moon was, humanity was fascinated by it. This intrigue forms part of the foundation for 'The Moon' exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in London.

Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr, lunar module pilot of the first lunar landing mission

The astronaut poses for a photograph beside the deployed United States flag during Apollo 11

'This exhibition is about humankind's relationship with the moon expressed through culture,' says Melanie Vandenbrouck, curator of art at Royal Museums Greenwich and the lead curator of 'The Moon' exhibition. 'What we really wanted to express is how the moon is part of the human DNA and how everyone who has and will ever live will have done so under the light of the moon.'

Researchers believe that as far back as around 15,000 years ago, people attempted to represent the lunar phases in the famous cave paintings at Lascaux. One of the exhibition's oldest objects on display is from Mesopotamia, dating to 172 BC. Through exploring imagery related to the moon across periods and regions, we get an interesting insight into different mythologies around the world.

The Roman goddess Diana was somewhat of a conglomeration of several Greek mythological figures, including the moon goddess Selene. In the story of Endymion – sometimes told with Selene and sometimes with Diana – the goddess asks Zeus to place the shepherd Endymion into an eternal sleep so that she might lay with him each night. In a painting by Edward John Poynter in the Manchester Art Gallery collection, we see Endymion sleeping on a forest floor while Diana floats in the background. She is nude, but carries a sheer shawl that billows behind her, mimicking the shape of the large full moon to her back. It's not dissimilar to scenes from fairy tales with sleeping princesses that we're familiar with today.

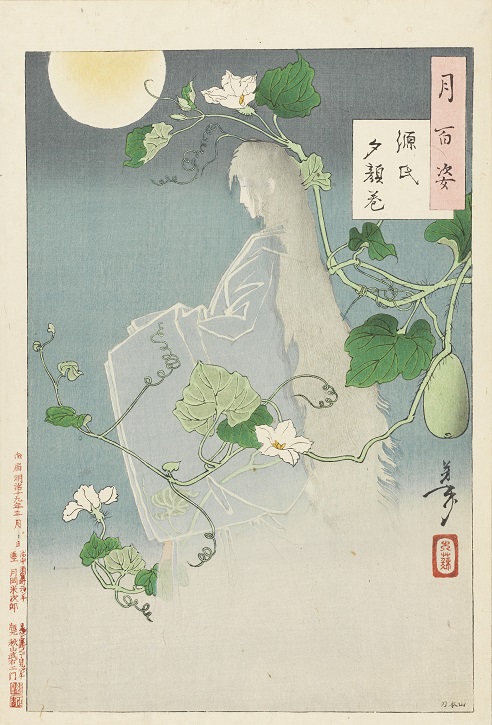

Genji yûgao no maki ('The Yûgao chapter from The Tale of Genji')

from Tsuki hyakushi ('One Hundred Aspects of the Moon'), 1886, print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892)

Even in Japan – a country known as the 'land of the rising sun' – the moon holds a special place within its culture. '[There is] a festival celebrating the Harvest Moon in autumn, for instance,' says Melanie. '[And] moon-viewing platforms and gardens with gravel that is raked in such a way that it captures the light of the moon in the most beautiful manner.'

In the classic Japanese story Tale of Genji, one chapter centres on a beautiful maiden and poetess who lives in a garden of moonflowers. The title character Genji falls in love with her, but the maiden, who he calls Yûgao (moonflower), is killed by the ghost of a jealous mistress. The nineteenth-century artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi chooses to depict Yûgao in her series of 100 paintings of the moon, showing the maiden alongside the flowers and a glowing moon.

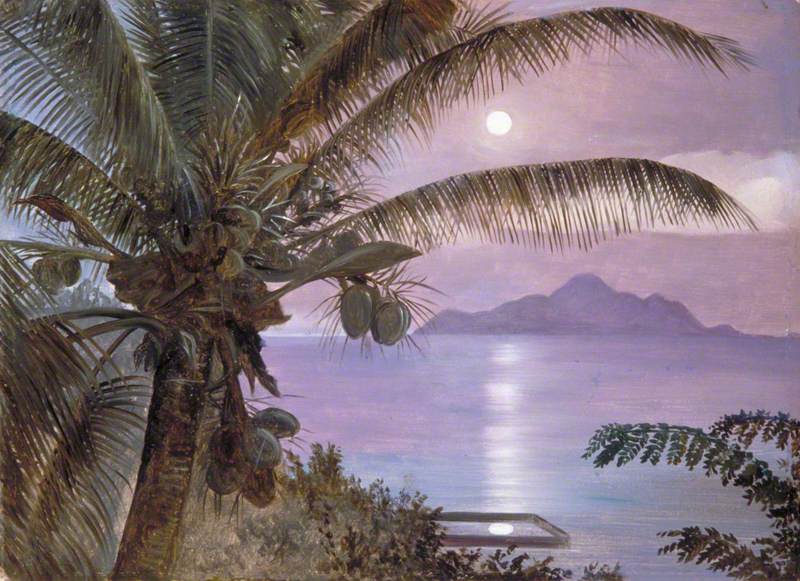

It wasn't only myths of the moon that inspired artists. The shining orb casting a dreamy light across landscapes has inspired artists for centuries. In a painting by Claude-Joseph Vernet in the Ashmolean Museum collection titled Coastal Scene (La nuit), the artist shows a bustling harbour scene at night, lit by a full moon. Eighteenth-century travellers on the Grand Tour in Italy were large collectors of these moonlit seascapes, which led to their popularity in Britain. J. M. W. Turner came along not long after Vernet, and he also occasionally drew inspiration from the moon. The first two paintings he displayed at the Royal Academy in 1796 and 1797 were moonlit seascapes.

The Moon

c.1787, pastel by John Russell (1745–1806)

'In 1609, shortly after the invention of the telescope, two men – Thomas Harriot in England and Galileo Galilei in Italy – look at the moon through the lens of a telescope and discover a geological world of craters and mountains and valleys,' says Melanie.

Artists' skill for rendering light and shadow would become very useful for scientists to represent this geological surface in an age before photography. With the aid of a telescope and the advice of prominent astronomers of the time, some of the earliest detailed drawings of the moon were carried out by John Russell, an eighteenth-century pastel portraitist. This relationship between art and science is one that continues. Artist James Naysmith, for example, carried out a similar project to John Russell by painting sunspots in 1860.

Fast-forwarding to the age of the Space Race, NASA formalised this relationship by creating the NASA Art Program in 1962. Its purpose was to document space exploration through an artistic lens. More than 350 artists were given access to information, enabling them to create portraits, abstract works, imaginative moonscape scenes and more. Amongst the artists that participated were Annie Leibovitz, Robert Rauschenberg, Norman Rockwell, Andy Warhol, and others.

First Woman on the Moon

1999, photograph by Aleksandra Mir (b.1967)

Outside of these NASA commissions, many artists around the world continue to be captivated by man's journey into space and reflect this interest in their work. Aleksandra Mir took umbrage with the lack of diversity on the moon and created her own lunar surface on a Dutch beach, making herself the first woman on the moon. She was followed by the first German, gay man and black man on the moon. Wrapped up in ideas and imagery of the moon is a human element that connects us to each other, where the moon becomes a symbol for something greater.

'The moon – across time, across history, across cultures – can be seen as this great mirror of human emotions and passions and endeavours, and trying to reach beyond our limits,' says Melanie. 'In fact, it seems to me that when we look at the moon, what we are really looking at is ourselves.'

'The Moon' exhibition at the National Maritime Museum is open until 5th January 2020.

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes