This online exhibition examines what it means to exist as embodied creatures, a reality especially apparent in the midst of a global pandemic, and how variations in bodily experience have manifested in art. All works of art are from the University of Dundee Museum Collections.

Larynx

MacKinnon provides an unfiltered view of a vital part of the human body: the larynx, or “voice box.” Without it, humans would hardly be able to sing or speak, and, if the larynx is removed, air can no longer pass from the lungs into the mouth. In her oil painting, she points to the startling complexities held within the human body and the functions which we consider everyday or mundane but which are sustained by seemingly alien structures.

Katie MacKinnon (b.1985)

Oil on canvas

H 214 x W 224 cm

University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

Stomach

Like MacKinnon, McCreadie also depicts a vital, familiar structure, the stomach, outside of its bodily context, rendering it as unfamiliar—this time through sculpture. Her entire group of themed sculptures, depicting bodily forms like teeth, a hairy mole, and cracked heels, was presented in a medical cabinet.

Rachel McCreadie (b.1994)

Nylon & polystyrene

H 12 x W 13 x D 26 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

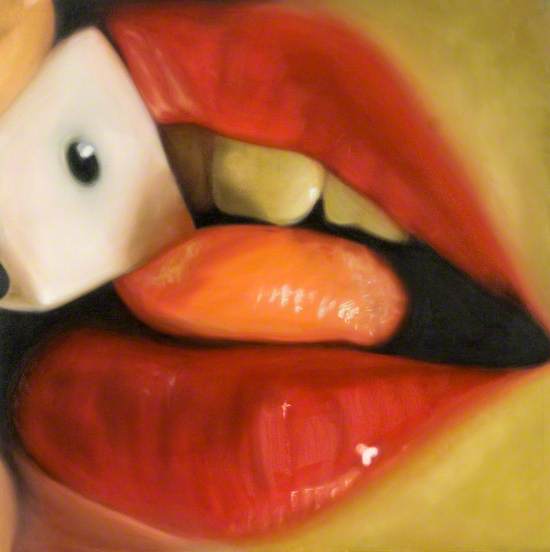

Die

Fletcher explores what it means to taste and feel through this intimate encounter with the human mouth. Kissing or licking dice is a common ritual to bring about good luck, as is likely the case in this mysterious scene. However, this moment is allowed to linger—permitting the viewer to notice the imperfect angles of the teeth, the shine of the lips. The side of the die being shown, one, suggests a sense of longing for a single object of affection, coupled with the title “Die.” Some would argue that to love is to experience a form of death to self.

Jonathan Kris Burton Fletcher

Oil on canvas

H 92 x W 92 cm

University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

.

Country Dances (Symphonic Form)

This gorgeous painting depicts a tableau of scenes in a range of artistic styles, bridged by the common motif of dance. Collins celebrates the body’s capabilities, showing it as a vessel for joy, pleasure, and self-expression. Depicted in the centre is the Hindu god, Shiva, known as the “lord of the dance.”

Peter Godfrey Collins (1935–2023)

Oil on board

H 119 x W 180 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

.

Figures Pulling Rope

Three bodies in motion can be seen, arresting in their geometry. While emotive, there is something about the scene that appears to be plucked from a physics textbook—serving as a lesson in momentum, leverage, and force. The body is shown as a tool, an agent of change, operating synchronously in community.

unknown artist

Acrylic & pencil on paper

H 15 x W 31 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

.

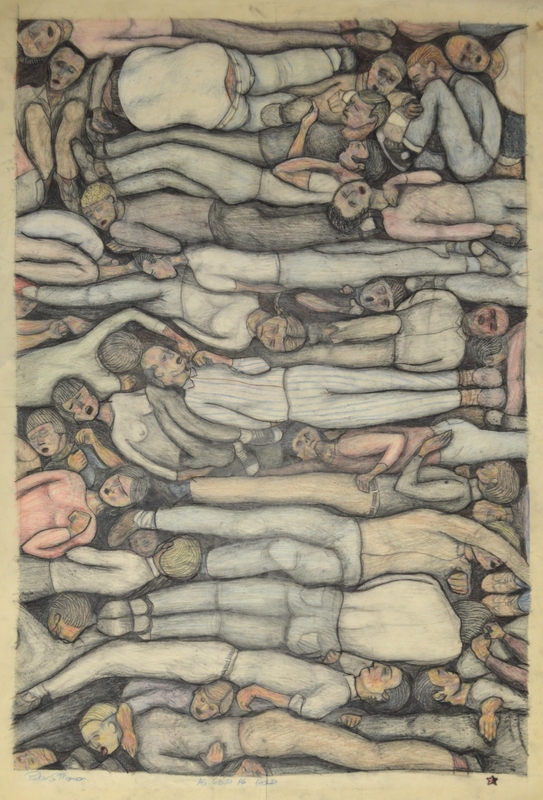

As Good as Gold

The true diversity and interconnectivity of humanity is on display in Thomson’s piece. We do not live in isolation, a notion increasingly present in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Thomson depicts this principle with his bodies piled upon bodies: a reminder that we all collectively share in life and death as humans of all different ages, ethnicities, and personalities.

Peter Thomson

Oil on canvas

H 206 x W 132 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

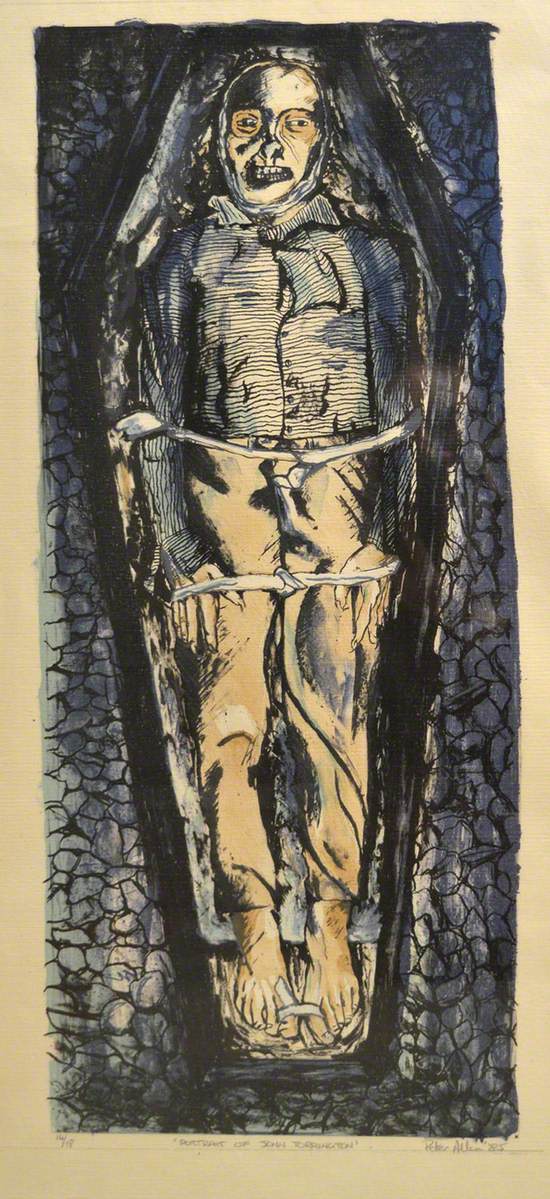

John Torrington (1825–1846)

Petty Officer John Shaw Torrington was a Royal Navy stoker. He was part of an expedition to find the Northwest Passage, but he died early on in the trip and was buried on Beechey Island. His preserved body was exhumed in 1984 in order to try to determine the cause of death, inspiring this posthumous portrait. In it, his corpse grimaces, bound and appearing to be frozen.

Peter Allan (b.1965)

Lithograph on paper

H 64 x W 26 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

.

Back to Front

The amoebic shapes in Watson’s artwork are mysterious, resembling pathogens. They ominously emphasize how the body is vulnerable and can be overtaken by illness. This sense of foreboding is heightened by the artist’s use of black daubs and slashes of red, like blood. Micro and macro levels seem to coexist, with germs or microbes existing at the same scale as the human torso.

Nicola Watson

Oil, watercolour & pencil on paper

H 151 x W 156 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

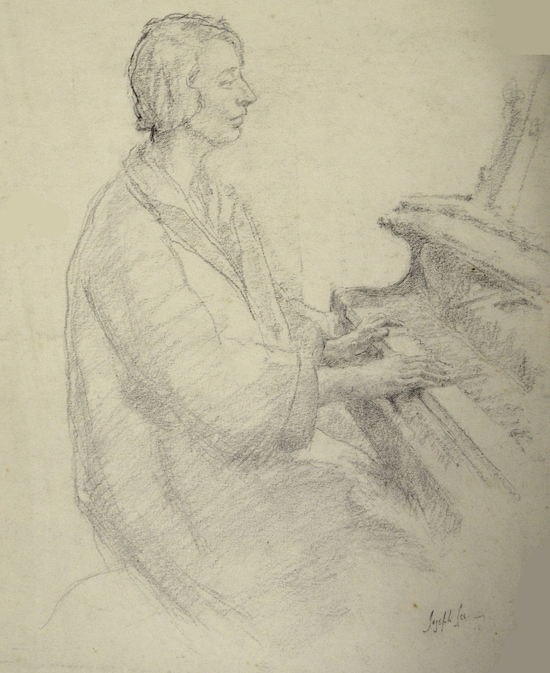

Woman Sitting at the Piano

Lee captures a moment of delicate intensity: a woman seated at a piano, her eyes transfixed by the sheets of music in front of her and her fingers curved over the keys to play a beautiful melody. It is up to the viewer to decide if it is a lively jig or a slow anthem of longing. Her face reveals no sign, simply her lips fixed in concentration.

Joseph Johnston Lee (1876–1949)

Pencil on paper

H 38 x W 28 cm

University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

.

Portrait of John and Celie

Byrne challenges our traditional expectations of bodily proportions, elongating the man’s form and adding curves to the woman resembling jodhpur breeches used for twentieth century horseback riding. The mood is somber and contemplative, reflected in the dark, earthy tones. John and Celie’s gazes are fixed in opposite directions, suggesting a sense of drifting apart that is unusual in portraits. As the poet Ocean Vuong writes: “The most beautiful part of your body / is where it’s headed.” The audience rightly wonders: where is this? Will the siblings’ paths diverge?

John Byrne (1940–2023)

Acrylic on canvas

H 150 x W 100 cm

University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

Untitled

In Scrimgeour’s series “La Souillure” (meaning “The Tainted”), the body is obscured in varied dripping colours, raising questions of what is beauty and what is disfigurement. She fractures the paradigm of idealised women. In this oil painting, the eyes indeed serve as the window to the soul—the only aspect of the person that the artist allows to remain clear and untouched.

Lisa Scrimgeour

Oil & spectragel on paper & board

H 183 x W 123 cm

University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

Male Life Study

In media today, the bodies of aged individuals are often shunned or deemed taboo or lesser. MacLennan creates a dignified but vulnerable scene of a man in the latter years of life. In his face, one can see conflicting emotions of contentment as well as reservation.

Alastair Mackay MacLennan (b.1943)

Oil on board

H 213.5 x W 91.5 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

Female Nude Study

In a similar manner that age is often shunned, diverse body types are also marginalised. Duke paints a woman in contemplation whose body is unapologetic. While the chair beneath her and the background remain unfinished, Duke prioritises representing the body in its entirety and showing it as a thing of beauty, worthy of taking up space.

Michelle Duke (b.1967)

Oil on canvas

H 91 x W 61 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

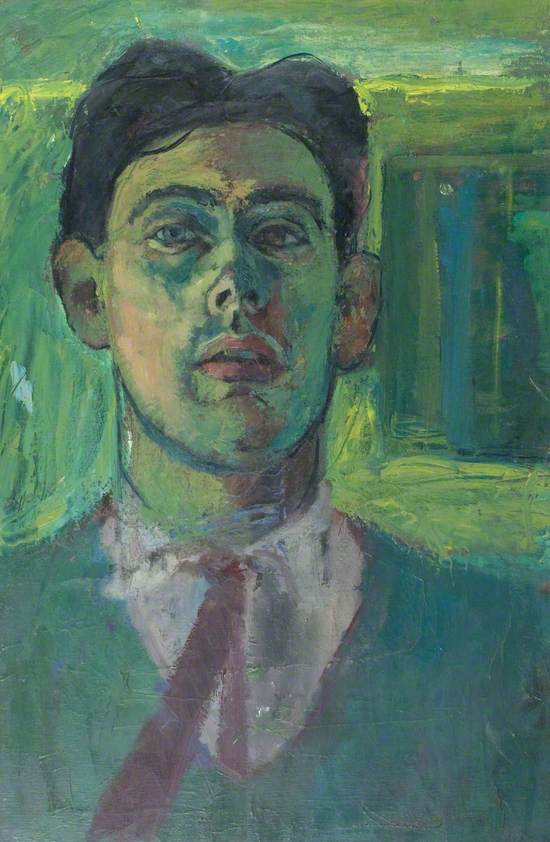

Self Portrait

In a style reminiscent of Edvard Munch, McIntyre depicts himself in somewhat shocking shades of green. Interestingly, he also paints himself as green in his Self Portrait with Bedroom Mirror (c. 1964). The psychological connotations of the colour green include freshness and growth but also negative emotions such as envy. His unusual facial expression is inscrutable and difficult to interpret. What does he feel? Disgust? Surprise? Regardless, while many self-portraits appear smug or confident, McIntyre’s self-portrait is a reminder that sometimes the body can catch one off-guard or is not what one expects or is pleased to see.

Joe McIntyre (b.1940)

Oil on canvas

H 73.5 x W 48 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

Estado de gracia

Andrew Hay's Colour & Warmth exhibition staged by the Tayside Medical History Museum in 1998 displayed Hay's work with patients at Ninewells Hospital. He was inspired to paint this portrait of Hugh McColl (known as Shuggy). Shuggy, then in his mid-twenties, was unable to speak or control the movement of his limbs. Hay was struck by the intensity of Shuggy's expression and drew parallels to El Greco’s painting of Christ: El Expolio. This extraordinary painting was the result: a rare portrait of a disabled person present in a public art collection.

Andrew Hay (b.1944)

Oil on canvas

H 149 x W 102 cm

University of Dundee, Tayside Medical History Museum Art Collection

.

Untitled

In Corvi’s sculpture, the female body is depicted kneeling. The woman leans and appears to be tying her hair into a bun. There is something Grecian about her form and movement, and terra cotta was actually first used during this era. Terra cotta is a rather breakable medium, which speaks volumes about perceptions of women and their fragility as well as the general precarious nature of being embodied.

Pierangela Corvi

Terracotta

H 17 x W 7 x D 13 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

Untitled

Through sculpture, Dalziel challenges our conception of the body. As our eyes track upwards, we are able to make sense of the form’s legs but the rest of the visual equation quickly falls apart. Is the figure without a head? Without arms? What truly makes up the body? How much can we remove before the body becomes something else entirely?

Matthew Dalziel (b.1957)

Wood, stone & tape

H 43 x W 22 x D 15 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

.

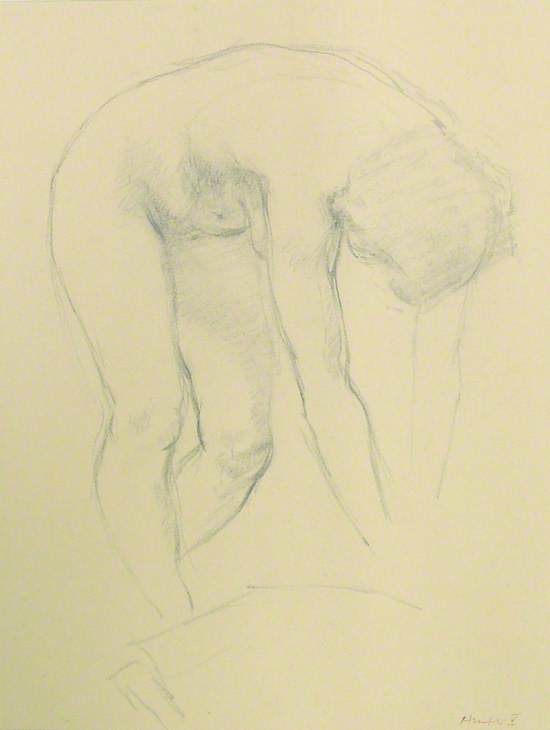

Female Nude

In this sketch, the woman appears completely unguarded as she bends over, perhaps to pick an item up or prepare a bath. This is the body in its raw beauty—unpolished and unadorned. There is no obvious posturing or sucking in one’s stomach. She is allowed to just be.

Richard (Dick) Hunter (1935–2014)

Charcoal on paper

H 30 x W 23 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

.

Male Nude

Gordon’s duality of red and green in the background is striking, perhaps representing two sides of human nature. The man is caught between, bare both physically and emotionally. He appears to have come to a decision between the two options, glancing towards his left, into the green, where both of his arms are also placed.

Patricia Gordon

Oil on board

H 151 x W 90 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

Richard III (1452-1485)

The University of Dundee is internationally renowned for its work in forensic facial reconstruction. This painting is a take on the original paintings of Richard III, which were not actually painted from life. As a “model,” the artist used a forensic facial reconstruction of Richard created for the documentary “The King in the Car Park” by researchers at the University of Dundee's Centre for Anatomy & Human Identification.

Janice Aitken (b.1962)

Acrylic on canvas

H 46 x W 36 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

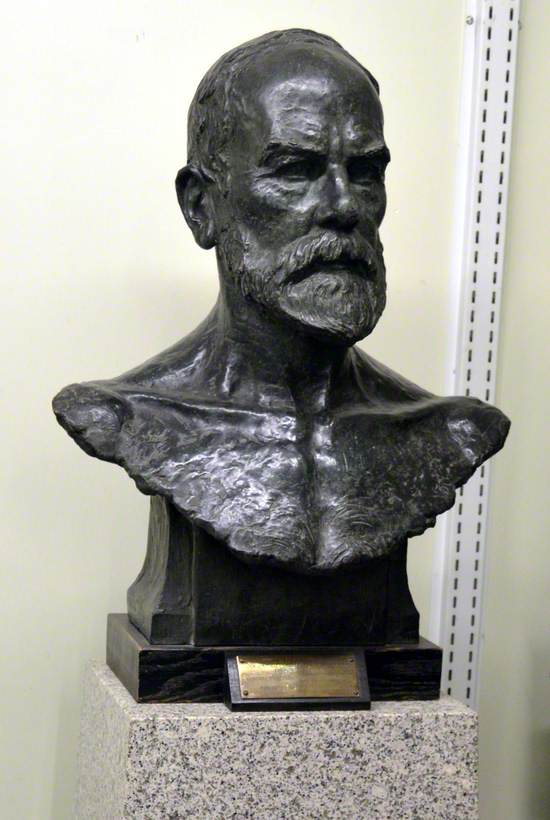

Sir James Mackenzie (1853–1925), MD, FRS, LLD, General Practitioner and Cardiologist

Sir James Mackenzie was known as the father of modern cardiology. His bronze bust is cast with a certain intensity and severity. Uniquely, Mackenzie is depicted with a naked chest, perhaps to suggest where he would have placed his stethoscope or to create a sense of proximity with the cardiologist’s own heart.

Louis Frederick Roslyn (1878–1940)

Bronze

H 68 x W 53 x D 30 cm

University of Dundee, Tayside Medical History Museum Art Collection

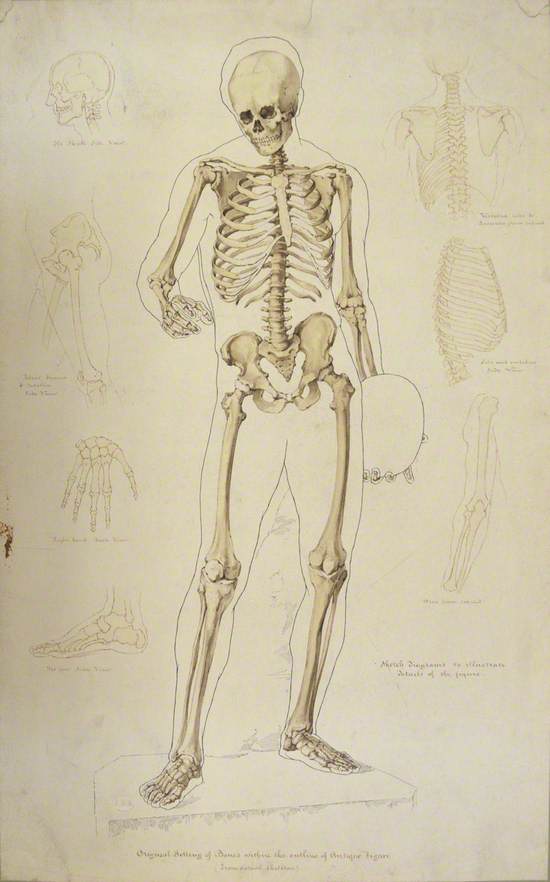

Original Setting of Bones within the Outline of Antique Figure

This is a standard exercise for the Science and Art Department at South Kensington, created by an art student at Dundee Technical Institute around 1895. The outline is that of Discobolus (discus thrower) by Naukydes. Around the main body, the ribs, vertebrae of the back, neck, hand, leg, and foot can all be seen in greater detail.

unknown artist

Pen & ink on paper

H 74 x W 55 cm

University of Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College Collection

Explore artists in this Curation

View all 21-

unknown artist

unknown artist -

Louis Frederick Roslyn (1878–1940)

Louis Frederick Roslyn (1878–1940) -

Andrew Hay (b.1944)

Andrew Hay (b.1944) -

Michelle Duke (b.1967)

Michelle Duke (b.1967) -

Peter Godfrey Collins (1935–2023)

Peter Godfrey Collins (1935–2023) -

Janice Aitken (b.1962)

Janice Aitken (b.1962) -

Peter Thomson

Peter Thomson -

Patricia Gordon

Patricia Gordon -

Nicola Watson

Nicola Watson -

Katie MacKinnon (b.1985)

Katie MacKinnon (b.1985) - View all 21