During the Second World War, the Houses of Parliament were damaged by air raids on 14 different occasions. The Palace of Westminster saw damage to Old Palace Yard and St Stephen’s Porch. But the worst destruction occurred on the night of the 10th May, into the early hours of the 11th May 1941. Lives were lost, and the House of Commons Chamber was destroyed.

This curation tells the story of the worst night of the Blitz through works held by the Parliamentary Art Collection.

10th May, 1941

That night, the skies over London were clear, and the moon was bright. Over seven hours, 505 German bomber planes followed the silvery path of the River Thames to drop more than 700 tons of high explosive bombs and 86,000 incendiary bombs across London.

The Houses of Parliament were hit several times, and three people on duty in the House of Lords lost their lives.

unknown artist

Watercolour on paper

Parliamentary Art Collection

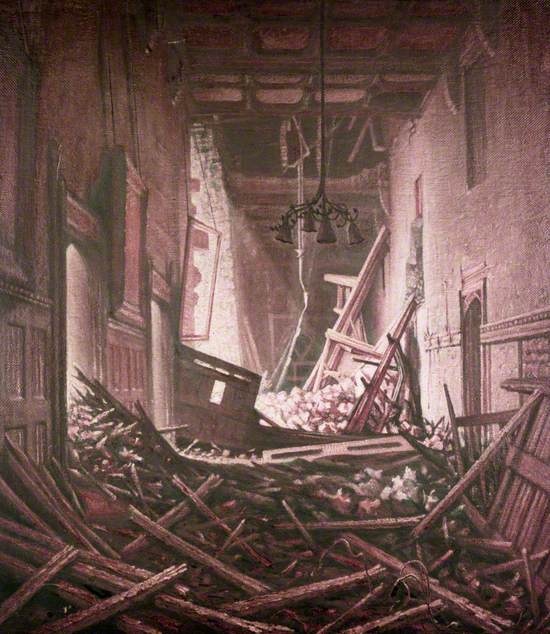

Bombs hit the House of Commons. The Members’ Lobby, which had already survived a direct hit in a previous air raid, was struck again. The roof collapsed, and fire quickly spread through the Commons Chamber.

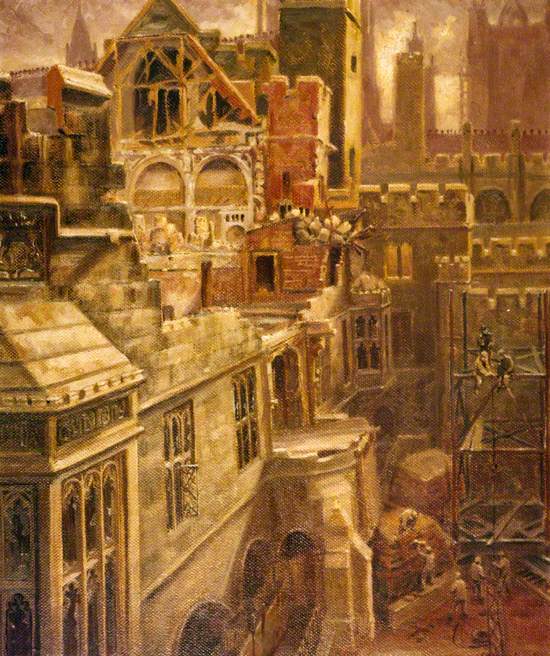

Meanwhile, falling incendiaries were threatening Westminster Hall. The Medieval wooden hammer-beam roof had caught fire.

As more than 50 fire service pumps and their crews struggled to contain the huge blazes, the fire service realised it would be impossible to save both the Chamber and the Hall.

William John MacLeod (1891–1970)

Oil on hardboard

H 147.3 x W 121.9 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

Walter Elliot (1888-1958), a former Cabinet minister, hurried over from his nearby home and directed the fire fighters to save the Hall. He personally used an axe to smash through the doors of the Hall to enable hoses to be brought inside and save the burning roof.

These paintings by William John MacLeod (1891-1970) depict the attempts to stop the blaze. Just visible are the figures of firefighters among the streams of water and clouds of smoke.

MacLeod studied at Glasgow School of Art before volunteering to fight in World War 1. He was discharged following injury and spent 10 years in recovery. During this time, he served as a war artist.

William John MacLeod (1891–1970)

Oil on hardboard

H 70 x W 57.5 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

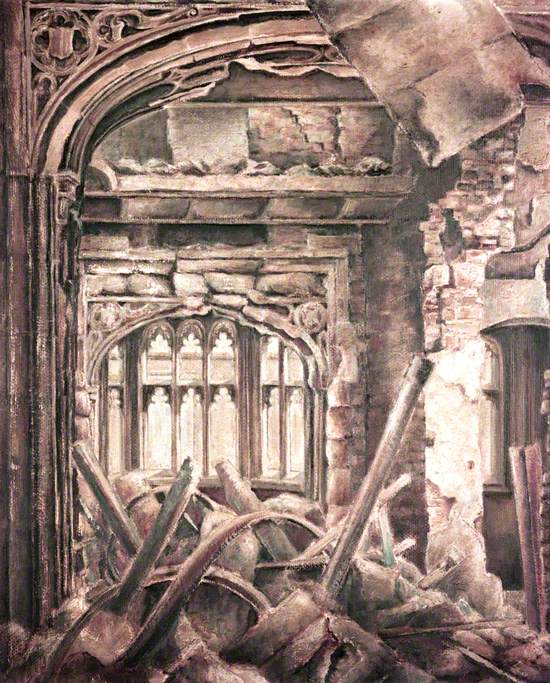

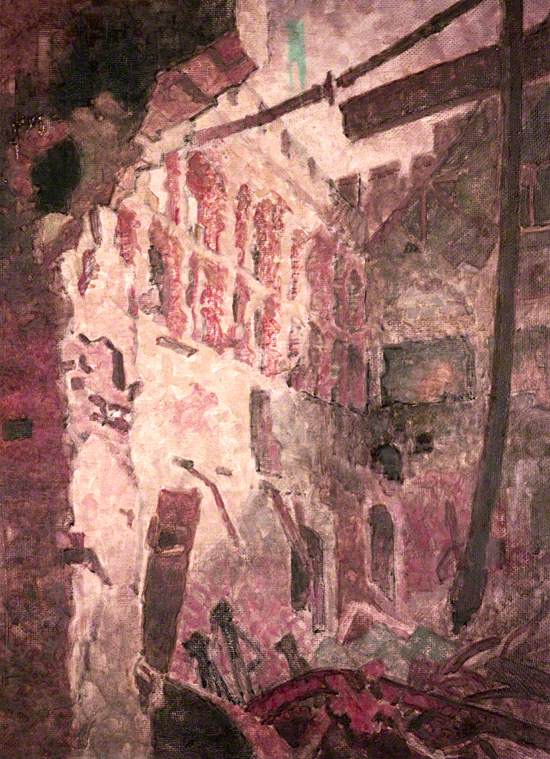

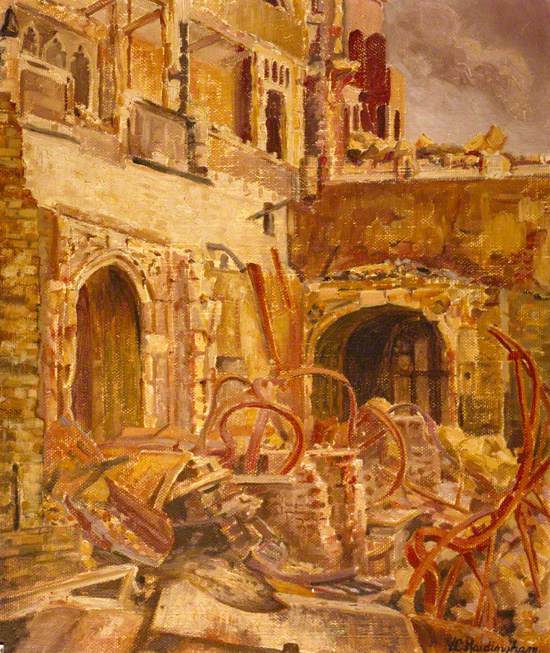

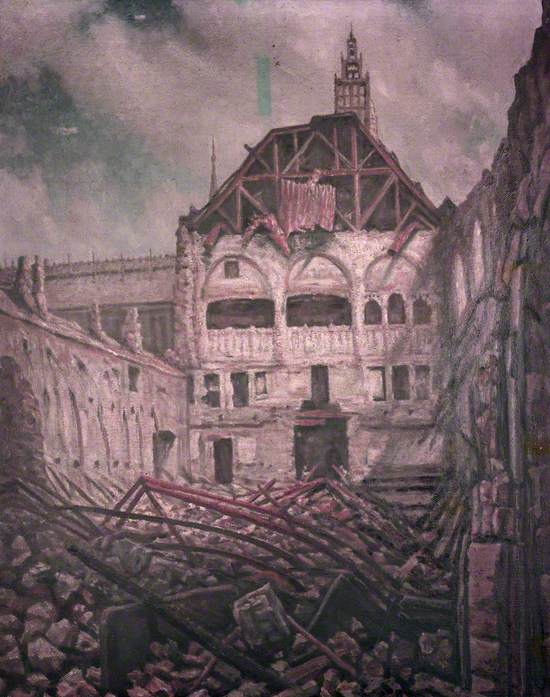

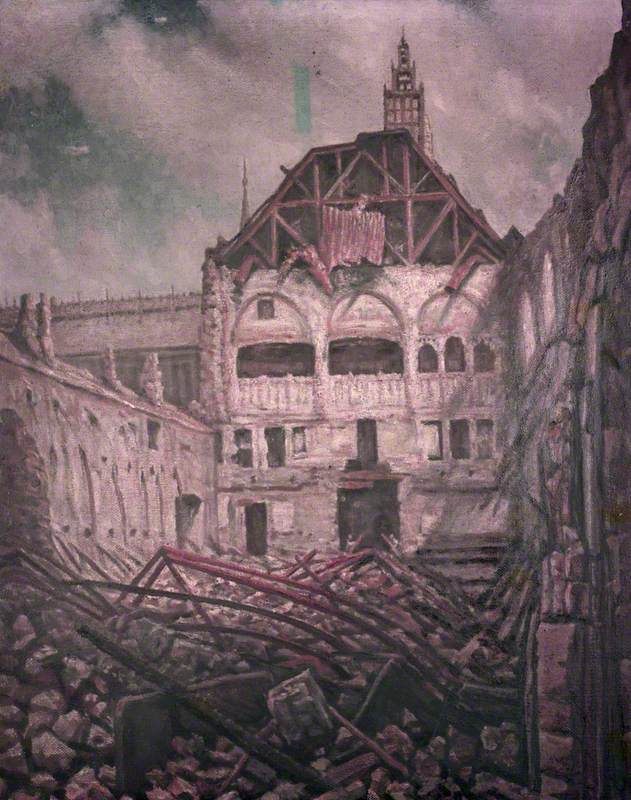

The all-clear sounded at 5.50am on the morning of 11th May. As the day rose, the devastation of the House of Commons was revealed. The Chamber had been completely destroyed by the fire. The whole Westminster area was shrouded in dust.

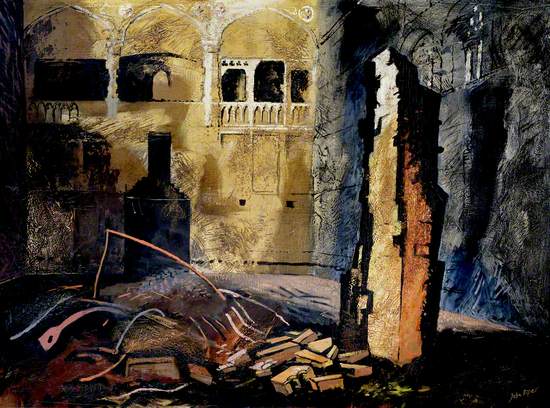

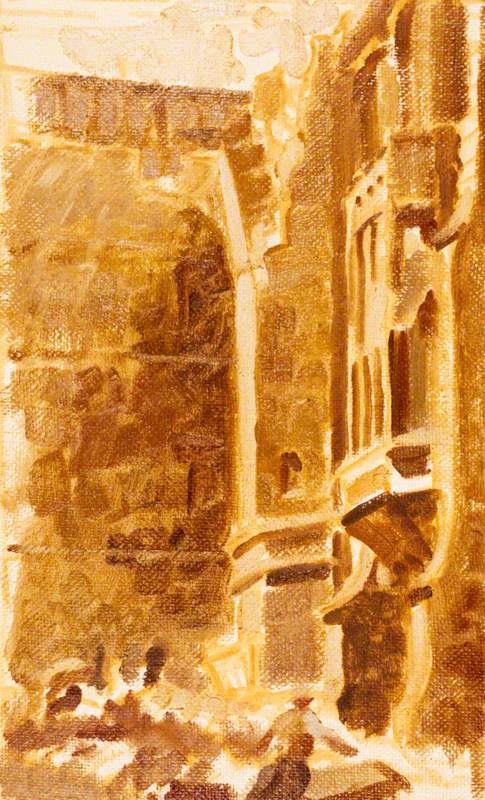

The Ministry of Works asked artists to document the scene. A series of works of art show us the extent of the damage to the Palace. They capture torn and tangled metal amidst chunks of fallen masonry. The Chamber is rendered unsalvageable.

Arthur Shearsby

Oil on hardboard

H 60.9 x W 49.5 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

C. C. Cole (active 1941–1942)

Oil on hardboard

H 41.9 x W 46.9 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

Vivian Charles Hardingham (1893–1972)

Oil on hardboard

H 70 x W 50.8 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

William John MacLeod (1891–1970)

Oil on hardboard

H 58.4 x W 72.4 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

C. C. Cole (active 1941–1942)

Oil on board

H 59.7 x W 44.4 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

Vivian Charles Hardingham (1893–1972)

Oil on hardboard

H 60.96 x W 50.8 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

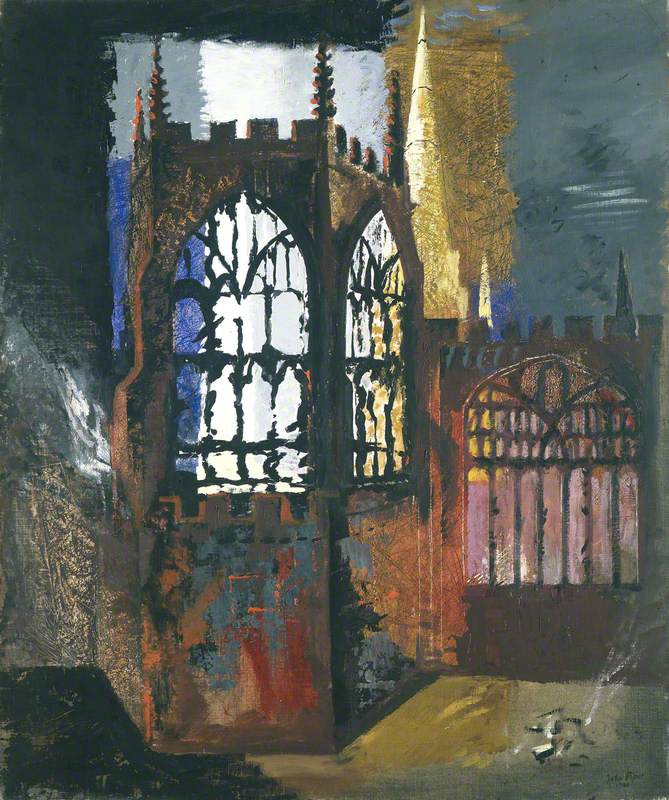

John Piper (1903–1992)

Oil on canvas

H 91.4 x W 121.9 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

William John MacLeod (1891–1970)

Oil on hardboard

H 86.3 x W 76.2 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

The loss of the Chamber did not stop Parliament from continuing to work and fulfil its essential role at the height of war.

From late June 1941 until October 1950, the Commons met in the Lords Chamber, while the Lords met in the Robing Room. This was kept secret during the war, as was the schedule of sitting days.

William John MacLeod (1891–1970)

Oil on board

H 94 x W 76.2 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

Frank Beresford (1881-1967) documented the scene at the House of Commons as it was cleared for rebuilding. Beresford painted the view looking south, towards Central Lobby. You can see figures busy at work, clearing rubble. The entrance to the House of Commons is also visible under the scaffold in the centre.

In a letter to the Ministry of Works, dated 28 April 1957, Beresford describes the painting as: “…a historical record, done on the spot at the time, having that authenticity which no subsequent ‘made-up’ picture could possibly have.”

Frank Ernest Beresford (1881–1967)

Oil on canvas

H 86.5 x W 99 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

It took many years to rebuild the Chamber. This work captures the hard labour of clearing the metal from the ruins.

The new Chamber was designed by architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880-1960). He was guided by Winston Churchill’s insistence that the space remain laid out with opposing sides, and without designated seats. Churchill believed the Chamber should be adversarial, stating: “we shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us”.

Vivian Charles Hardingham (1893–1972)

Oil on hardboard

H 76.2 x W 116.8 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection

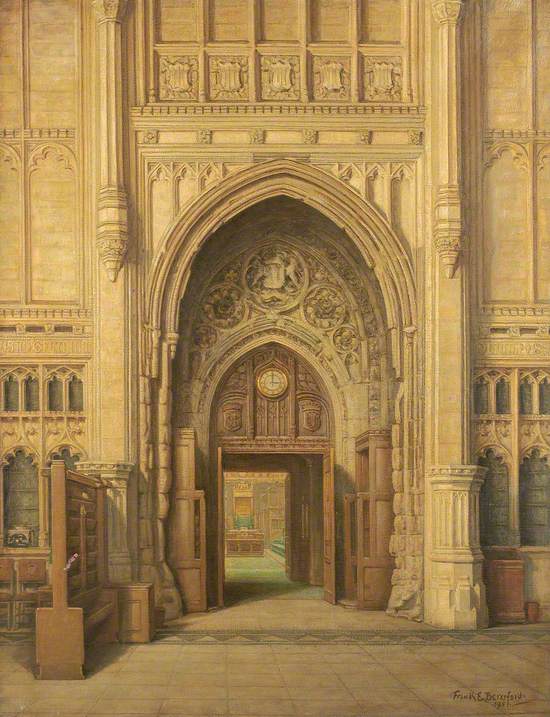

The Churchill Arch

Artist Frank Beresford notes in his diaries: “The ‘House’ was hit and had to be demolished before rebuilding could safely be started again, and at Churchill’s suggestion the entrance to the Chamber from the Lobby was to be replaced stone by stone in its damaged condition as a lasting symbol for all to see and remember.”

Beresford's painting shows the view from the Members’ Lobby looking into the rebuilt House of Commons Chamber, through the Churchill Arch. The new Chamber was used for the first time in October 1950.

These works of art capture the scale of destruction that the Palace survived in 1941.

Frank Ernest Beresford (1881–1967)

Oil on canvas

H 113 x W 85 cm

Parliamentary Art Collection