What is a castle?

Worldwide, castles have had many purposes and meanings. They may be coveted possessions of strategic and political importance, symbolising power, sovereignty and conquest. They are sites of attack, defence, vigilance; places of imprisonment, but conversely also of protection, sanctuary and refuge. They may conceal mysteries, secrets, even atrocities within their walls, or become museums committed to revealing hidden stories of the past.

This Curation responds to a loan from the National Gallery, London of The Fortress of Königstein from the North by Bernardo Bellotto (1756-58) to Norwich Castle Museum in summer 2021. It explores some of the themes above, using a wide range of artworks from medieval to contemporary.

Power

Originally, most castles worldwide were intended as sites where power was exerted and retained. A castle may be a potent symbol of victory in war, a metaphor for the ruling dynasty, which surveys the surroundings from the vantage point of castle battlements, imposing its will on both land and people.

The Fortress of Königstein from the North

This view of the fortress of Königstein, south-east of Dresden, is one of the five commissioned from Bellotto by King Augustus III of Poland in 1756.

In this work Bellotto combines minute, beautifully rendered details of people going about their daily tasks with a broad panorama. Bellotto was from Venice, and applied the traditions of Venetian view painting – a high level of detail, a large scale – to this landscape. However, Bellotto also emphasises this fortress’s towering strength and dominance. He places it so that it dwarfs everything else, forcing everyone, including the viewer, to look up towards it. Soldiers watch from the top ramparts, keeping close surveillance of the land around.

Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780)

Oil on canvas

H 132.1 x W 236.2 cm

The National Gallery, London

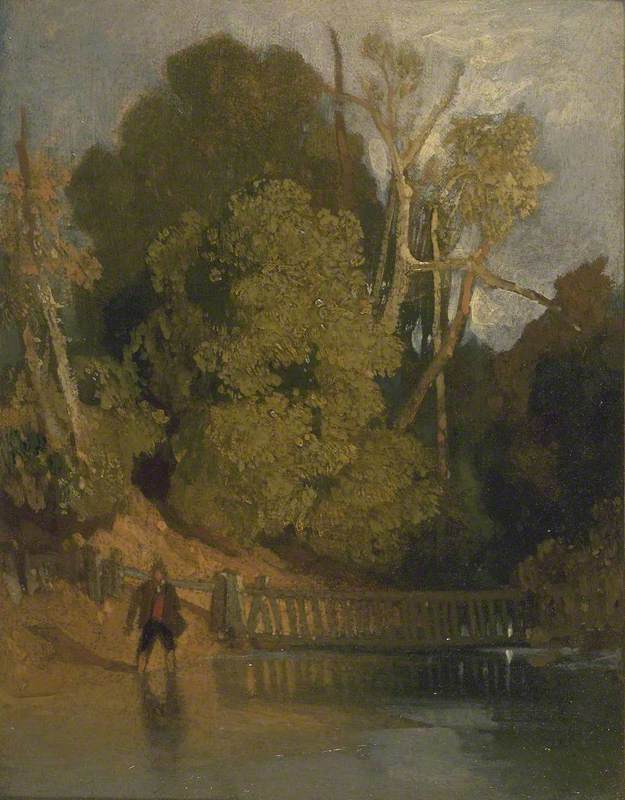

Landscape with Norwich Castle and Cathedral in the Distance

In this tranquil rural scene, Norwich Castle looms large, visible even from several miles away. The cathedral is also clearly recognisable. Both these buildings, having existed since the 11th century CE, were ever-present reminders of the twin forces of church and state which completely ruled ordinary peoples’ lives. The castle's square solidity underlines its rule over the earthly plane.

Crome may not have intended his work to make a statement about power. Nonetheless it is a clear reminder of how dominant a presence such buildings had, when they were so much larger than everything else. Today, when the area is built up, the impact is far less obvious, but people in the past had these buildings constantly in their field of vision.

William Henry Crome (1806–1873)

Oil on oak panel

H 65.8 x W 91.5 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

.

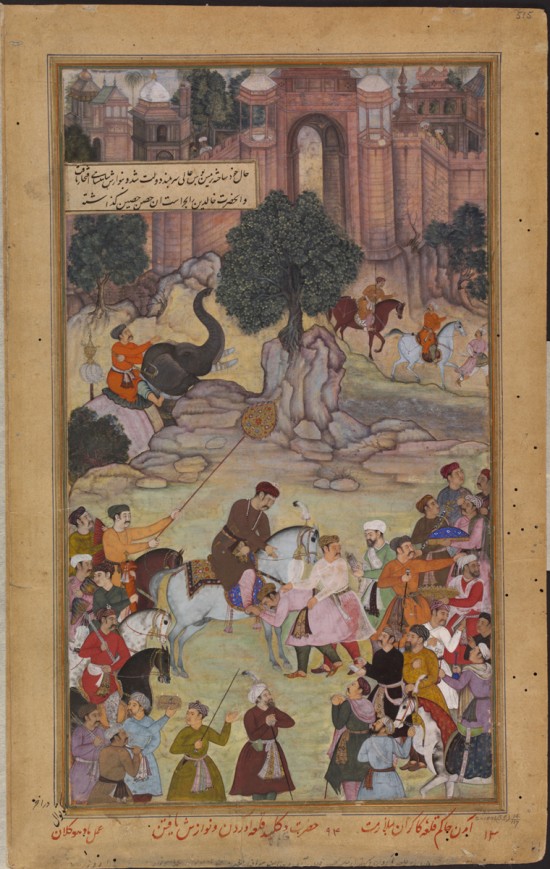

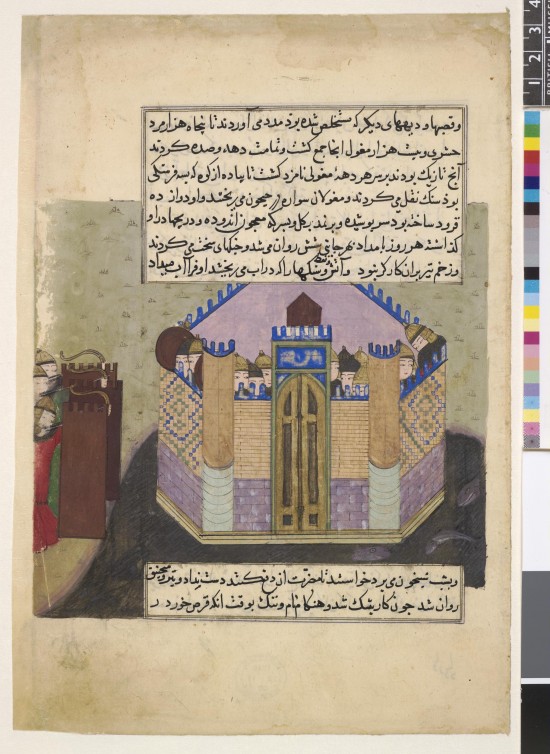

The Governor of Gagraun, in Kotah, Rajasthan, submitting the keys of his fort to Emperor Akbar in 1561

This painting depicts the symbolic importance of castles. The narrative explains that the governor of Gagraun was so overawed by Emperor Akbar that he surrendered his fortress without a fight.

Handing over the keys is seen as an act of submission. The governor bows humbly. His castle is shown with its doors wide open, literally and figuratively allowing access to Akbar’s army.

Akbar (1542-1605) was one of the greatest of the Mughal rulers. A soldier, politician and social reformer, he was also a noted art patron. He commissioned the Akbarnama from historian Abu'l Fazl ibn Mubarak as his official biography. The pages in the V&A’s collection are thought to be part of the first illustrated copy, intended for Akbar’s own library.

_The Governor of Gagraun, in Kotah, Rajasthan, submitting the keys of his fort to Emperor Akbar in 1561_, c. 1590-95, Madhav Kalan, Mughal Empire, Opaque watercolour and gold on paper, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

.

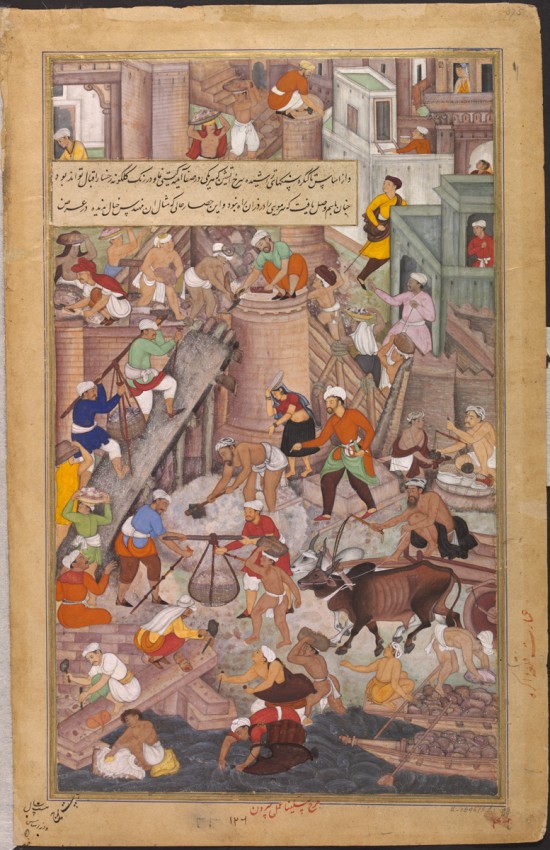

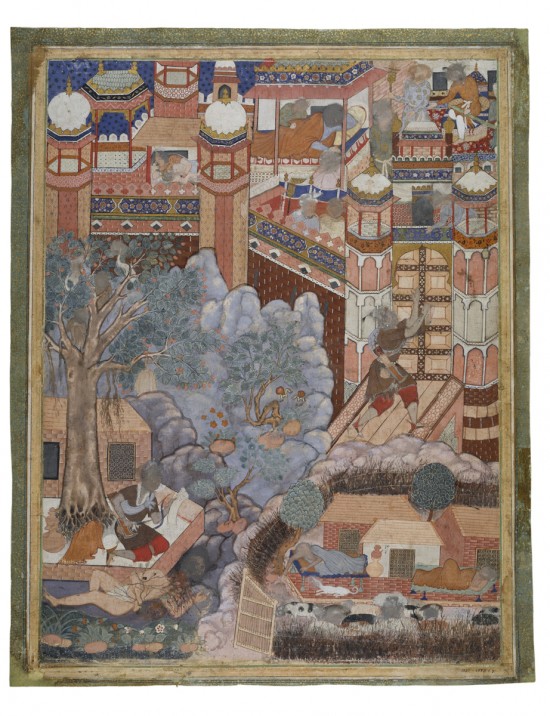

The Building of the Fort at Agra

The fortress at Agra, being in a strategically significant position, was a politically crucial possession. It was captured by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in 1556. Like successful rulers worldwide, he soon set about re-building the fort, to make it stronger and more magnificent, to enhance its prestige and his own. Several thousand workmen took eight years to finish the new castle, the Akbarnama states, to the highest possible standard.

This picture is a fascinating depiction of a sixteenth century building site, full of lively details of the men at work. This busy scene demonstrates not only the key importance to a ruler’s identity and image of creating a splendid castle, but also the sheer quantity of raw materials and human labour needed.

_The Building of the Fort at Agra_, c. 1590-95, Miskina & Sarwan, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

.

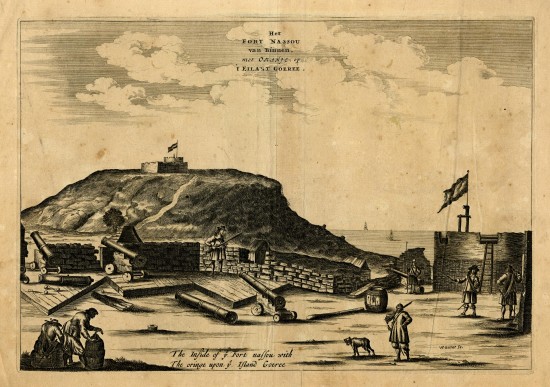

The inside of ye Fort Nassau with the Oringe upon ye Island Goeree

This print and the next in the Curation are illustrations from a Dutch book of world topography and scenery. Built by Europeans, the two castles portrayed, in Ghana and Senegal, were important colonial centres for several centuries, with successive European owners, including Portuguese, Dutch, French and English.

From the seventeenth century these coastal castles in Elmina and Goree played a major part in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans. Thousands of captured people were imprisoned here before being shipped off overseas.

_The inside of ye Fort Nassau with the Oringe upon ye Island Goeree_ (from the series La Galerie Agréable du Monde), c. 1668, Incorrectly attributed to Wenceslaus Hollar, published by Pieter van der Aa, etching and engraving on paper, British Museum,

.

Casteel del Mina

The castles at Elmina and Goree held thousands of enslaved people, but no Africans are visible in either picture. These prints contain 'hidden histories'. There is no trace of what the castles were being used for at the time these prints were made, or the absolute power their owners wielded over peoples' lives.

Elmina Castle in Ghana still exists and is now a major museum documenting the history of slavery. It contains one of the infamous ‘Doors of No Return’ seen in several surviving European coastal castles of Africa once used for the transatlantic trade.

_Casteel del Mina_, (from the series La Galerie Agréable du Monde), c. 1668, incorrectly attributed to Wenceslaus Hollar, published by Pieter van der Aa, etching and engraving on paper, British Museum

.

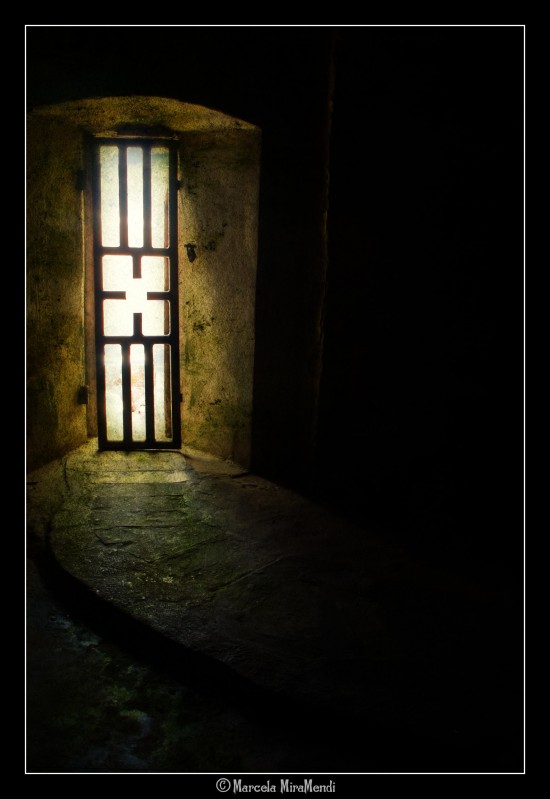

The 'Door of No Return'

‘Doors of No Return’, like this one, featured as part of the coastal castles. Enslaved people were taken out through these doors and forced on board ships to leave their native land forever. They now form key focal points in African museums of slavery such as those at Elmina, Christiansborg, Cape Coast and Dakar. The doors are of particular significance for African-American visitors, many of whom go back through them to symbolise their return to connect with their ancestral roots.

Probably the most famous recent visitor to do this was Barack Obama, who visited with his family in 2009.

'Door of No Return', Elmina Castle, Ghana

Attack and Defence

Castles were originally designed to provide a place of strength from which to resist attack and to counter-attack enemy forces. The castles in this section are all historical, rather than imaginary, and some still exist. They could be places of sanctuary to keep people safe during times of war.

However, these pictures illustrate castles’ vulnerabilities just as much as their strength. Most could be defeated eventually, given sufficient forces and an appropriate strategy. Königstein, as featured in Bellotto's painting, was an exception: it bore the nickname of 'the Bastille of the North', and it was never defeated in battle.

Ubbergen Castle

Aelbert Cuyp’s vision of Ubbergen Castle portrays it as a ruin, but it was at the time an important national monument. Attacked and ruined in 1582 during the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands, it was seen as a symbol of national independence. This work was probably painted in 1655, less than a decade after the Treaty of Münster (1648), when the Dutch finally won independence from Spain.

Cuyp has employed the same soft colour palette and mottled patterns to depict the crumbling walls as for the landscape behind. The reflections in the lake add to the impression that the ruined castle is merging peacefully with its surroundings, following its central part in the recent conflict.

Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691)

Oil on oak

H 32.1 x W 54.5 cm

The National Gallery, London

Castle in Yorkshire

While in north Yorkshire during 1803-5, John Sell Cotman produced some magnificent watercolours. He was inspired by some of the best-known architecture and ruins of the county, and the sites he chose included several castles.

The identity of this one is unknown, but it demonstrates clearly how the boundaries between a castle and a fortified house were frequently blurred. While England and Scotland were enemies, before 1603 when James I succeeded Elizabeth I, the northern English feared attacks from the Scots.

During the Civil War castles which had fallen out of defensive use were used again, as Yorkshire played a significant role in this war. Charles I had moved his court to York in 1642 and much of the county was strongly royalist.

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Watercolour on paper

H 24 x W 33.3 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

.

The Siege of Khujand

This painting depicts the siege of Khujand in 1220 CE, by Mongol forces led by Čengiz Khan. The city of Khujand, in modern-day Tajikistan, was a major administrative and cultural centre, in a strategically favourable position for trade and agriculture. It was thus important to control and was attacked several times during its history.

The painting is from a chronicle of the Mongol Empire by historian ‘Ata-Malik Juvayni. Though unfinished, it portrays universal elements of siege warfare with superb directness and visual economy. The castle’s inhabitants peer over the battlements. There is little detail in the foreground but the fish indicate the castle is moated. Čengiz Khan’s archers, meanwhile, are attacking from behind a wooden shield.

_The Siege of Khujand_, from the Tarikh-i Jahan Gusha, 1438, Anonymous, Persian School, Painting on paper, British Museum

.

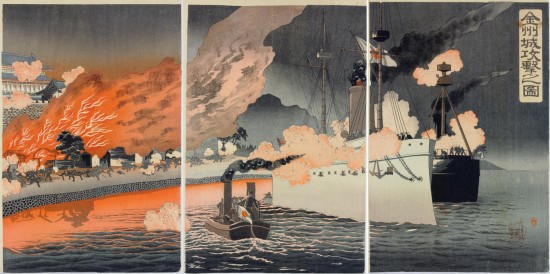

Attack on Jinzhou Castle by Japanese ships

This dramatic print portrays the attack on a strategically important Chinese castle during the first Sino-Japanese war. The colours, restricted to black and red, provide the perfect means to express the fire’s fierce power, magnified to twice actual size by its reflection, and lighting up the night. The huge battleship placed diagonally across the image, initially less noticeable than the fire, is an additional layer of menace.

This work shows how any castle, however strong, may be defeated with the right strategy. In 1894 the Japanese army took Jinzhou within an hour. Even if we did not know the outcome, the picture conveys a sense of doom. The building itself, visible only in one corner, is almost engulfed, its men tiny and helpless.

_Attack on Jinzhou Castle by Japanese ships_, 1894, Adachi Ginko (active 1874 - 1897), published by Tsujiokaya Bunsuke, Ink on paper, British Museum

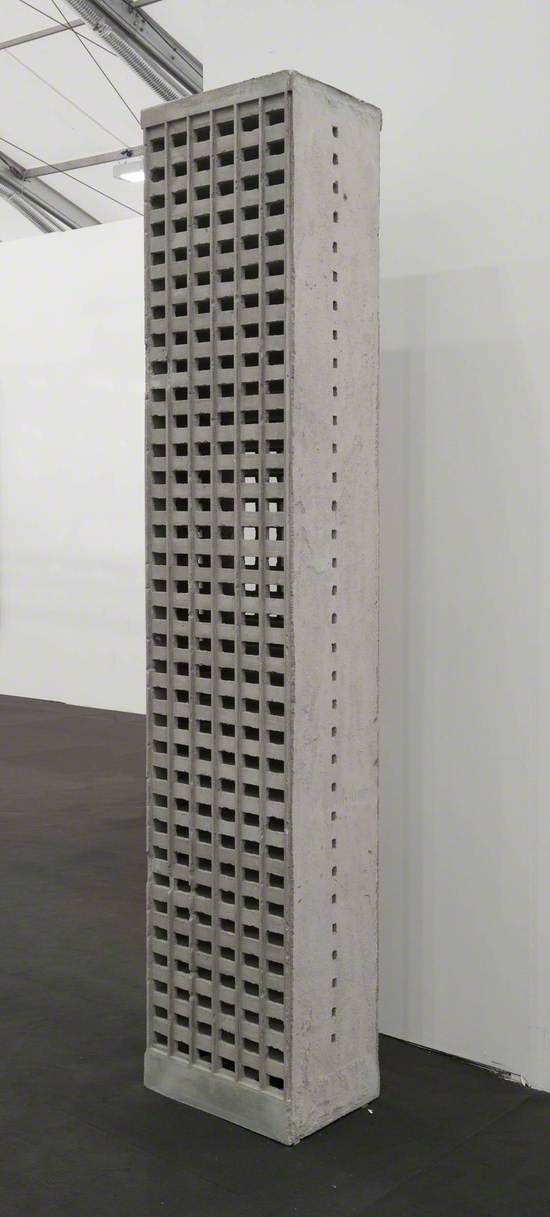

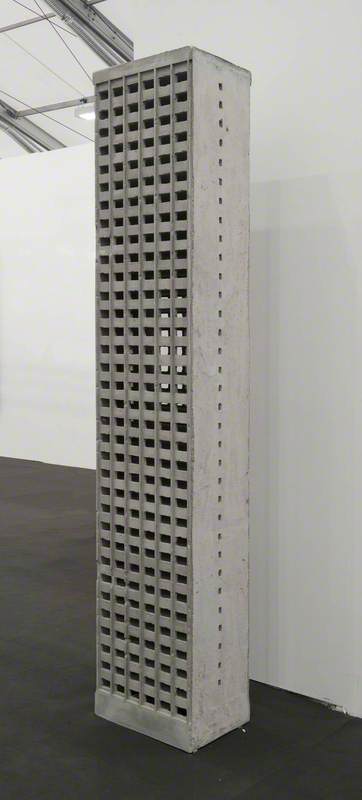

Monument for the Living

Castles do not need to be purpose-built for use in war. Marwan Rechmaoui's work depicts Beirut's iconic Burj al Murr. Though built as an office block it was only ever used as a sniper post, during the Lebanese civil war. Rival soldiers occupied a similar building, a hotel nearby. In effect, these were two opposing fortresses, their height giving them the strategic advantages of the more traditional hilltop castle.

The Burj al Murr, with its distinctive architecture, features in work by many prominent contemporary Lebanese artists. Its position in an urban area makes it dangerous to demolish, so this de facto castle survives, its use and future uncertain. Rechmaoui's title reflects its significance within recent history.

Marwan Rechmaoui (b.1964)

Concrete & wood

H 236 x W 60 x D 40 cm

Tate

Ruin

In the present day, probably the most usual way for us to see a castle is as a ruin. Many artists have been attracted to the romantic vision of a ruined castle, an image of decayed magnificence set within dramatic natural surroundings.

Sometimes little more than a few stones of the original building remain. This may make us think about the processes of ruin, which may be natural or deliberate, gradual or brutally sudden. However strong ancient structures might be, they were never designed to resist modern warfare. Today, they are rendered more vulnerable than ever before in history.

Adoration of the Kings

In this painting the three Kings, Balthasar, Caspar and Melchior, present their gifts to the Christ Child in the ruins of a grand building. In the background a view of an unidentified contemporary northern European town is visible.

It may perhaps seem strange that David has sited his nativity scene in a ruined medieval castle rather than in a Bethlehem stable as the biblical story states, but it was customary at the time for artists to portray religious scenes in contemporary contexts. Most importantly, this ruined castle is symbolic, and central to the painting’s meaning. The ruin represents the old order of the world, now replaced by the new hope of the Christian faith which Jesus’ birth heralded to Gerard David and his contemporaries.

Gerard David (c.1460–1523)

Oil on oak

H 60 x W 59.2 cm

The National Gallery, London

Burgh Castle near Yarmouth, Norfolk

Artists in the Romantic period of the early nineteenth century usually focused on ruins’ aesthetic qualities, to add a picturesque or pensive touch to a landscape. Here the ruined Burgh Castle, with Breydon Water in the background, conveys a relaxed atmosphere. A man leans casually on the wall, as if it is so familiar it is scarcely noticed.

Burgh Castle was once a Roman cavalry fort, built in the third century CE for coastal defence. Its strategic position on the Waveney estuary meant it was later used by the Normans. Today, it is an important, well-preserved archaeological monument. Crome, if he knew the fort’s history, was probably less interested in this aspect than he was in the Romantic idea of a relic surviving from ancient times.

John Berney Crome (1794–1842)

Oil on mahogany panel

H 25.1 x W 34.1 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

.

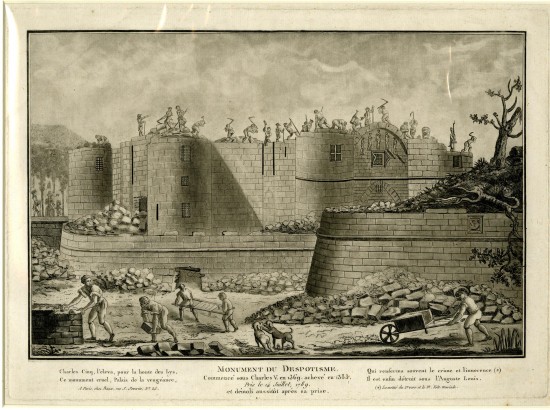

Monument du Despotisme

This print portrays the demolition of the Bastille during the French Revolution. At the time, the Bastille was a prison, not a royal palace, and had long since ceased to be directly associated with the current royal family. For the revolutionaries it still symbolised the hated regime. They deliberately ruined the building. Its stones were reused, metals melted down, and souvenirs sent around France. This showed that the rule of the country now belonged to its people, not an elite.

Castles may evoke sovereignty and the prevailing social order. The people expressed their rage by ‘killing’ the Bastille. They would have hoped to encourage the revolutionary effort, showing how individuals working together can topple even the strongest force.

_Monument du Despotisme_, 1789 Anonymous, published by Jacques Louis Bance, etching and aquatint on paper, British Museum

Kett's Castle, Norwich

This ruin is St Michael’s Chapel, which overlooks Norwich on the hill known as Kett’s Heights. Robert Kett was a yeoman farmer. In 1549 he led a revolt in protest against growing hardships caused by rent increases and land enclosures.

Kett gathered a huge following. He wrote to King Edward VI demanding better conditions for the poor. He was refused, so the rebels attacked Norwich, from this base near the city. Their attempt failed, and Kett was hanged from Norwich Castle battlements.

Kett maintained he was loyal to the king, and wanted only social justice. He is unlikely to have referred to his own camp as a ‘castle’. But in the bleak grandeur of this ruin, and its sombre colours, Cotman has captured some of the sadness of Kett’s story.

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Watercolour on paper

H 22.1 x W 32.5 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

.

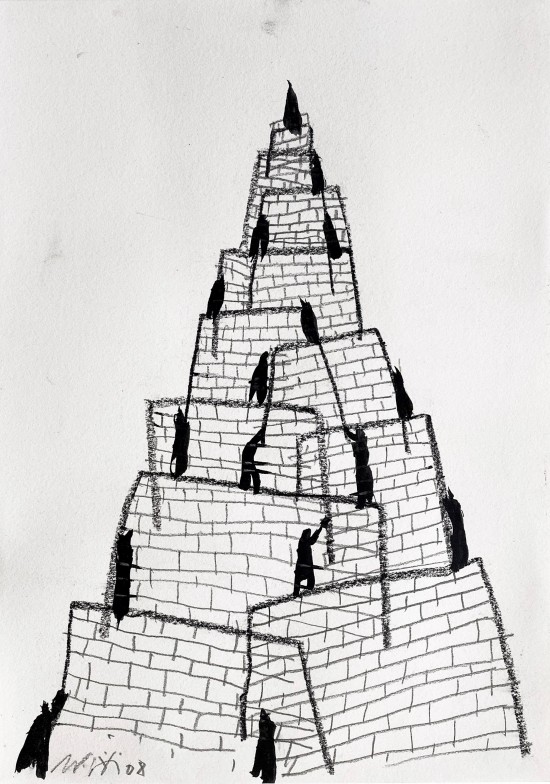

Tower

Walid Siti’s castles closely reference geometric Islamic art traditions, but also resemble the Tower of Babel. They emphasise the fragility of historic buildings and the practice of their deliberate destruction, as happened most recently in the artist’s native Iraqi Kurdistan.

Another main influence is the minaret of Samarra, one of the most famous works of ancient architecture in existence. Built in the 9th century CE, this minaret still stands, but was damaged by both American and Iraqi troops during recent conflict, after being used as a military base.

Dark, ominous soldier figures on this tower occupy the entire structure. They show how irreplaceable heritage may be obliterated, whether as an act of war or mere ‘collateral damage’.

Tower Series, No. 12, 2008, charcoal and acrylic on paper

Tales and Mysteries

Worldwide, castles inspire stories. The designs of these intriguing buildings, whether ruined or whole, have always engaged the imaginations of artists and writers. The literal complexities of a castle’s architecture reflect the metaphorical twists and turns of a plot for an audience to enjoy.

A castle lends itself to every type of fairy-tale. It is an indispensable backdrop to stories of supernatural villains, from Dracula to Bluebeard: a gift to the film director! Heroines like Cinderella and Snow White, having married their princes, live happily ever after in a castle. With magic around every corner, a castle can become a character in its own right.

Saint George and the Dragon

Here Moreau depicts Saint George as a youth rather than a mature man. Although a warrior, George is also a figure of spiritual purity who, in killing the dragon to rescue the princess, is perhaps also vanquishing crude animal appetites.

The princess, praying high on a rock, seems at one with her turreted castle. Their airy serenity and pale colour palette contrast with the brighter colours and fierce activity of George’s battle with the dragon. As poised as a statue, the princess waits to be rescued. Here she is shown as an object of spiritual veneration not earthly lust, but her otherworldly appearance reminds the viewer that a woman’s role in such a story is traditionally passive. Princess and castle alike may be prizes for a victor.

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898)

Oil on canvas

H 141 x W 96.5 cm

The National Gallery, London

Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came

This painting illustrates a poem by Robert Browning. It describes Roland’s quest through a barren, nightmarish landscape to reach a mysterious tower.

In stories a quest usually has a purpose: to rescue a princess, slay a dragon, or seek the Holy Grail. In Browning’s poem the reason for the quest is unknown. We never find out what awaits Roland in the Dark Tower.

Roland’s climb up the narrow, steep track underlines the perils of his journey. We glimpse the castle in the distance, elusively positioned so we cannot see if there is any way to cross the ravine to reach it. Nonetheless, there is a flag flying from the tower, which adds to the unnerving atmosphere. It is inhabited, but by whom? What will Roland find when he finally arrives?

Briton Riviere (1840–1920)

Oil on canvas

H 126.4 x W 93.5 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

Castle by Water, or Ranza Castle

Cotman painted several Scottish landscapes, although it is not known if he ever visited Scotland. This castle, Lochranza, built in the thirteenth century, was small but well-fortified. It survives as a ruin today, cared for by Historic Scotland.

Apart from this picture, in art Lochranza is best known for inspiring an illustration for a story in the childrens’ series The Adventures of Tintin, by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. An image of the castle appears in The Black Island, which is set partly in Britain. Lochranza is not referred to by name, and why it was chosen specifically is not known. It may be that the artist was simply inspired by its rugged architecture and dramatic setting, as an archetypal castle of the romantic imagination.

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Watercolour on paper

H 26.4 x W 20.8 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

.

Basu beheads Namadpush and enters Acre Castle

A great artistic achievement of Mughal Emperor Akbar’s reign was the production of a monumental illustrated copy of the Hamzanama, the heroic adventures of Emir Hamza.

This page illustrates how one character, Basu, infiltrates himself into Acre Castle. The story contains many examples of gaining access to an enemy’s stronghold through disguise and daring subterfuge.

The unusually large size of this painting helps us to appreciate both the detail of the castle’s interior and the exciting twists of the plot. It may originally also have been intended as a visual aid to accompany readings by a storyteller. The layout resembles a graphic novel, following the course of the narrative by showing Basu in two different places simultaneously.

_Basu beheads Namadpush and enters Acre Castle_, ca. 1562-1577, artist unknown, India or Pakistan, gouache on prepared cotton backed with paper, Victoria and Albert Museum

Landscape with Psyche outside the Palace of Cupid ('The Enchanted Castle')

Claude portrays the classical myth of Psyche, a mortal so beautiful Cupid himself falls in love with her. He takes her to a magic castle full of treasure, visiting her only at night. He asks her never to try to discover who he is. Psyche’s sisters, jealous of her good fortune, urge her to find out. She lights a lamp to steal a look at her lover, accidently spilling hot oil on him as he sleeps. He flies away, leaving Psyche heartbroken. They are reunited only after many trials.

This work probably shows Psyche mourning her lost love, dwarfed by a castle which for all its magic is a lonely forbidding place. Claude combines real and imagined architecture to convey its eerie grandeur. Even tales with a happy ending have their frightening side.

Claude Lorrain (1604–1682)

Oil on canvas

H 87.1 x W 151.3 cm

The National Gallery, London

.

Rapunzel

This work is one of a series of self-portraits called True Tales, Fairy Tales in which Raeda Saadeh depicts herself as a fairy-tale character in a modern setting. As a Palestinian, she sets these stories in a specifically Palestinian context. Here she is Rapunzel, sitting by a ruin in Israeli-occupied territory. Her long hair ambiguously resembles a fetter, suggesting she is tied to her country’s conflicts but helpless to do anything about them.

However, this image may make us think more deeply about gender roles in fairy-tales, and at the fact that a woman herself may be compared to a castle. She is usually compelled to wait, either for rescue or to be occupied by an opposing force. A woman, like a castle, may become a spoil of war.

_Rapunzel_ Raeda Saadeh (b.1977), 2010, C-type photographic print on paper

.

Model of Castle or Temple

The original purpose of this beautiful and enigmatic model is unknown. It may have been intended as an architectural model, or perhaps have had a religious use, but its ultimate purpose remains a mystery.

Its minimalist simplicity makes it appear both ancient and modern. This model may remind the viewer that a castle building is in itself neutral. It may have a whole range of uses and meanings projected onto it by whichever individual may inhabit or conquer it.

Ceramic model of castle or temple, c1000-500BC, Anonymous, Asia, probably Azerbaijan, British Museum

.

Model of Norwich Castle

Jayden created this clay model of Norwich Castle when he was thirteen, as part of a young peoples’ art project run by the Castle’s Learning department. His interpretation of the building is simple but effective. He has captured the castle's solid, enduring qualities, summed up by its traditional nickname ‘the Square Box on the Hill’. This castle also resembles the thousand year-old clay model from Azerbaijan in the British Museum’s collection, featured in this Curation.

Jayden’s model serves as a reminder of the idea of the castle as a container, a box ready to be filled with stories and people, whether in reality or our imaginations.

Jayden (aged 13) _Norwich Castle_ Clay model, 2019

Castles Re-imagined and Re-made

Castles evolve. If they have not been allowed to decay into the landscape, many become museums, cultural centres, much-loved symbols of their locality and its histories. Such transformations may make a castle into a starting point for new ideas, or a new identity, allowing a castle’s hidden histories to be revealed fully for the first time in centuries.

The Castle of Muiden in Winter

In this painting, Beerstraten interprets the castle as powerful and impressive, but not threatening. Built for defence in the thirteenth century, by the date the picture was painted Muiden was one of the best-known medieval castles in Holland. Owned by a famous poet, it housed a noted literary group.

We view this castle from the north-east. The building is accurately portrayed, although the artist has altered the landscape. Looking from the north-east the sea would be behind the castle, but the artist needed the reflected light to pick out the front of the building and take the eye further into the distance.

No longer a literary centre, Muiden is today a popular museum. A castle’s use and identity may alter significantly over time.

Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraten (1622–1666)

Oil on canvas

H 96.5 x W 129.5 cm

The National Gallery, London

The Walls of the Alhambra, Granada

The Alhambra has undergone dramatic changes of identity. Built for the Muslim rulers of Granada, it became a Christian royal court when the Catholic monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, captured Granada in 1492. As a symbol of their conquest, they altered the palace significantly. Subsequent rulers adapted and rebuilt it. Napoleon’s armies used it as a barracks.

After this, the Alhambra was in poor repair. Probably unaware of its history of colonisation by both Spanish and French forces, Cotman would most likely have appreciated it as a semi-ruined, romantic relic. Today the Alhambra buildings form one of Spain’s most important monuments, a UNESCO site bearing witness to the country’s complex history and mixed Christian-Muslim past.

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Watercolour on paper

H 20.3 x W 13.3 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

.

Republic

Republic, from Gayle Chong Kwan’s Cockaigne series, conveys superficial perfection. This castle, with its fanciful design and kitsch colouring, seems an idyllic home fit for a princess from a cartoon film, until the viewer looks again and realises it is made from bread. It will quickly crumble, moulder and rot.

Chong Kwan’s work explores the search for paradise, as in the legendary Land of Cockaigne where all human needs are miraculously met. Here she has re-imagined a fairy-tale castle as a metaphor for meretricious illusion. Despite yearning for a perfect world, we may end up with an impossible, unsustainable fantasy, like the philosopher Plato’s vision of utopia in his famous work Republic, from which this picture takes its title.

Gayle Chong Kwan (b. 1973) _Republic_, 2004, C-type photographic print on paper

.

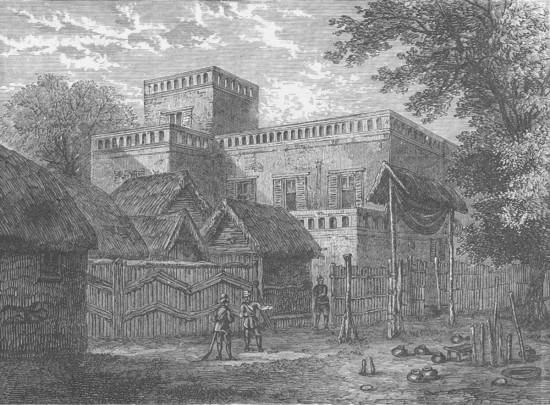

Kumasi Fort, Ghana

This fort was built in 1822 by Asantehene Osei Tutu Kwame Asiba Bonsu, king of the Asante, imitating a European-built Ghanaian coastal fort.

During the Anglo-Ashanti war of 1874 General Sir Garnet Wolseley looted and blew up Kumasi. He aimed to achieve “such a diminution in the prestige and military power of the Ashantee monarch as may result in the break-up of the kingdom altogether.” He was feted as a hero in Britain.

Kumasi’s stone was re-used by the British to build a new fort in 1897. They used it as an administrative centre until 1952, when they turned it into a military museum. Ghana gained independence in 1957, and the building is now the national military museum. Finally, Ghanaians have control over its use and interpretation.

Kumasi fort, Ghana, 1874; image titled 'King Koffee's Castle, Coomassie, 1874'

.

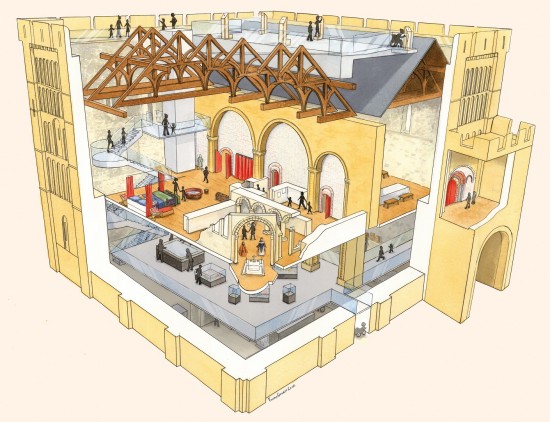

Norwich Castle as a Royal Palace

Castles may transform. If they are not allowed to decay into the landscape, or destroyed in war, many become museums, cultural centres, monuments, much-loved symbols of their locality. Königstein and Norwich Castle, along with others featured in this Curation, have this in common.

Castles retain traces of their past. Norwich Castle Keep is in the process of redevelopment, soon to reveal more layers of its history. Palace, prison, sanctuary, monument and museum, Norwich exemplifies the many identities and histories, some positive, some very dark, a castle may contain. As well as preserving buildings, the task of curators, archaeologists and educators today is to reveal these histories, putting them into context, for both present and future.

Norwich Castle as a Royal Palace - An artist's impression of the Castle Keep with the reinstated Norman layout, Fiona Gowen, 2019

Explore artists in this Curation

View all 11-

John Berney Crome (1794–1842)

John Berney Crome (1794–1842) -

Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraten (1622–1666)

Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraten (1622–1666) -

Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780)

Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780) -

Claude Lorrain (1604–1682)

Claude Lorrain (1604–1682) -

Briton Riviere (1840–1920)

Briton Riviere (1840–1920) -

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898)

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898) -

William Henry Crome (1806–1873)

William Henry Crome (1806–1873) -

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842) -

Gerard David (c.1460–1523)

Gerard David (c.1460–1523) -

Marwan Rechmaoui (b.1964)

Marwan Rechmaoui (b.1964) - View all 11